Three years ago i wrote about strategies for coping in the information age. The problem was volume: too many newsletters, podcasts, and articles competing for limited attention. My solution was a pipeline of filters and capture tools — Gmail, Readwise, Snipd, Notion — to tame the firehose so my brain could do the hard work.

That system worked well. But the world it was built for has moved on.

In 2023, the bottleneck was ingestion. In 2026, AI can do the hard work alongside you: reading unstructured information, applying what you know, producing something useful, checking it’s right. The frontier of what’s possible has moved. As Andrej Karpathy puts it: “The main effect is that I do a lot more than I was going to do because I can code up all kinds of things that just wouldn’t have been worth doing before.”

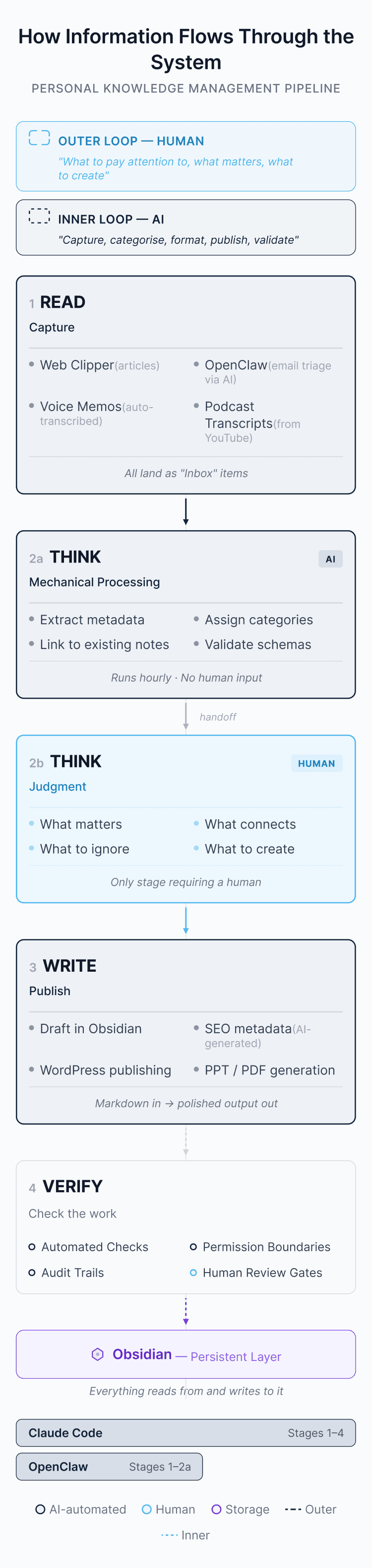

The way i think about it: there’s an outer loop and an inner loop. I run the outer — what to pay attention to, what matters, what to create. AI runs the inner — capture, categorise, format, publish, validate. The inner loop gets faster every month. The outer loop is where the value lives. This article is about how i set the loops up.

Why markdown matters

A core change since 2023 is storing everything in markdown — plain text with clear structure (headings, lists, code blocks) that both humans and agents read easily. No messy formatting means fewer agent mistakes. It’s lightweight, so it uses fewer tokens and costs less at scale. And because it’s an open format, agents work directly on your files. No API needed.

This sounds like a minor technical detail. It isn’t. It’s the foundation everything else depends on.

Why i left Notion for Obsidian

In 2023 i called Notion “mission critical” and predicted it would be one of the most valuable public companies in the world when it IPO’d. I still think Notion is a great product — and there are things i miss, particularly its collaborative databases and the slickness of its UI. But in January 2026, i migrated my entire knowledge base — roughly 10,000 files — out of it.

Over the Christmas 2025 break, agentic CLI tools became genuinely useful. Ben Horowitz captured the moment well: “Over the winter break, it turned a corner where really good programmers were going, ‘Whoa, oh god, this helps me.’ I can’t remember any kind of technology where all of a sudden you wake up and the whole world just changed like that.” And these agents work best with markdown files.

Notion stores your data in a proprietary format behind an API. Getting anything in or out programmatically is painful. Obsidian, by contrast, is just a folder of markdown files on your hard drive. No database. No API. No lock-in. Your notes are plain text files that any tool — including an AI agent — can read, search, edit, and create directly.

Steph Ango, the CEO of Obsidian, calls this “file over app” — if you want digital artefacts that last, they must be files you control, in formats that are easy to retrieve. I’d add: if you want AI agents to work with your knowledge, it needs to be in a format they can touch. The dividing line is shifting from open source vs closed source to open data vs closed data. Your knowledge base is either legible to agents, or it isn’t.

The migration was scary (Notion was my “second brain” after all). Over a weekend i had Claude Code import and restructure all 10,000 files — normalising metadata, assigning categories, removing duplicates. I ran multiple agents in parallel while i was on a hike. Came back to find the work done. Cost: over £200 in AI tokens. Worth it.

Claude Code: the bit that changes everything

Claude Code is a terminal-based AI agent from Anthropic. It has full access to your computer — reads files, writes files, runs scripts, browses the web. You tell it what you want in plain English and it works out how to do it. It’s closer to a very capable intern who lives in your terminal and never sleeps than it is to a chatbot.

Between December 2025 and January 2026, Claude Code went from 17 million to roughly 31 million daily active installs. I’ve used it daily since December. In my first month i logged over 2,500 sessions and 16,000 messages. It touched 13,000 files. I’m not unusual — SemiAnalysis estimates 4% of all GitHub commits are now authored by Claude Code, heading toward 20%+ by end of 2026.

Two things make it different from ChatGPT or any other AI assistant.

First, persistent memory. Claude Code loads its own markdown file of context every time it opens, so it doesn’t forget you. Every session picks up where you left off. This is the real shift from chatbots — not intelligence, but continuity.

Second, skills. These are reusable instruction files — markdown documents that teach Claude Code how to do specific jobs. I’ve built about 30 of them. When i say “turn this PDF into a PowerPoint,” it loads a skill that knows my formatting rules, layout logic, colour palettes. When i say “publish this essay to my website,” it loads a skill that knows my WordPress API credentials, taxonomy structure, and how to generate SEO metadata. The podcast transcript you might have seen on my site? Claude Code fetched it from YouTube, formatted it as an Obsidian note, and filed it — all from one instruction.

Unlike a chatbot, it executes. It ingests a podcast transcript, normalises the metadata, files it in the right folder, links it to related notes, and moves on to the next job. Tasks that used to take five tools and thirty minutes now happen in a single conversation.

The compounding is what excites and slightly terrifies me. Skills improve over time — there’s a reflect skill that analyses each session and proposes improvements to its own instructions. Hooks fire after every edit to validate metadata. Scripts run hourly to process incoming content without any human involvement. You stop using a tool and start managing a system that improves itself.

A caveat here, though — and it applies to anyone considering these tools, enterprises especially. Simon Willison has flagged prompt injection as the risk “most likely to result in a Challenger disaster.” These systems are powerful but easily manipulated. The more autonomy you give agents, the more important it is to understand what they’re doing and where the guardrails are.

How information flows through the system

The principle from 2023 still holds: be deliberate about what you consume, capture the best bits. The difference is that automation now extends deep into processing, not just capture.

READ: capture

Obsidian Web Clipper has replaced most of what Readwise used to do for articles. One click saves any web page as markdown in my vault, metadata included.

OpenClaw handles the email layer. This is an open-source AI assistant i run on a remote server, connected to my Gmail. Every morning it sends me a briefing via WhatsApp: calendar for the day, important emails, and which newsletters are worth reading. It auto-labels incoming mail, archives noise, and flags things that need a response. Every evening it sends a recap. It’s smarter than the Gmail filter rules from my 2023 setup because it reads the newsletter, not just the subject line.

Voice memos are now a proper pipeline. I record thoughts on my iPhone, iCloud syncs the audio to my Mac, and a background script sends it to Gemini for transcription. It extracts a title and topics, creates an Obsidian note, and links it to that day’s daily note. I record, forget about it, and the thought shows up in my vault later that day.

Podcast transcripts that used to take 15 minutes now take thirty seconds. I ask Claude Code to fetch the transcript from YouTube, format it as an Obsidian note with key quotes, and file it.

All incoming content gets marked as “Inbox” in my vault. Which leads to the next stage.

THINK: mechanical processing

This is where the agentic layer kicks in. When new material lands as “Inbox”, scripts run hourly to:

- extract key fields (source, author, date, topic)

- assign categories and topics

- remove the “inbox” marker

- link to existing notes via entity and concept matching

- validate schemas (so the vault doesn’t quietly rot)

For bulk operations, i use Claude Code’s parallel agents. When i had 436 unprocessed tweets after migrating from Notion, i didn’t sit there categorising them one by one. I launched six parallel agents and they worked through the lot in twenty minutes. The same pattern applies to any batch operation — normalising hundreds of book entries, cross-referencing meeting notes against project files, auditing vault health across 4,000+ notes.

THINK: judgment

AI handles mechanical thinking — categorisation, structuring, retrieval, pattern matching, first-pass synthesis. What it can’t do is the judgment: what matters, what connects, what to ignore, what to create.

Steph Ango makes a point about note-taking that i keep coming back to: “People have asked me if this could be automated with language models but I do not care to do so. I enjoy this process. Doing this maintenance helps me understand my own patterns.” He’s right. And this is the tension at the heart of the system: the more you automate, the more you risk losing the serendipity of slow processing. I’ve felt this — occasionally i’ll find that an agent has filed something i should have read properly, and the insight i would have had from reading it myself got lost. The goal isn’t to automate thinking. It’s to automate everything that isn’t thinking — but the boundary is blurrier than it looks.

WRITE: from notes to published work

Writing still starts with me. I draft in Obsidian — usually a plain markdown file. From there, Claude Code takes over. It generates SEO metadata, pushes the article to WordPress via an API, and handles the formatting. It knows my theme, taxonomy, and font stack. I tell it to publish and it publishes.

Presentations are the most dramatic change. I can hand Claude Code a set of notes or an article and it produces a branded PowerPoint — correct layouts, colour palette, formatted charts. It has a skill that can build PowerPoint files from scratch. The same workflow works for Word documents and PDFs. Markdown in, polished document out.

The gap between finished draft and published shrinks to minutes.

VERIFY: checking the work

Verification is non-negotiable. Karpathy describes LLMs as having “amusingly jagged performance characteristics — they are at the same time a genius polymath and a confused grade schooler.” You cannot skip verification just because the agent sounds confident.

In an agentic workflow, errors propagate — into files, artefacts, publications. So verification becomes a system design problem:

- Automated checks: link validation, formatting rules, schema compliance — agents run these after every edit

- Permission boundaries: explicit confirmation before destructive actions

- Audit trails: logs of what changed, when, and why

- Human review gates: publication, anything irreversible

The outer loop and the inner loop

Two systems now do what used to be entirely manual. Claude Code stretches from capture all the way through to publication. OpenClaw spans information triage through to processing. Underneath both sits Obsidian — the persistent layer that everything reads from and writes to.

What’s changed between 2023 and 2026 is which parts of this loop require a human. In 2023, you did all four stages yourself. Tools helped around the edges. In 2026, READ and WRITE are largely automated. VERIFY is increasingly automated. THINK splits in two: mechanical thinking is cheap; judgment remains scarce.

I run the outer loop — what to pay attention to, what matters, what to create. AI runs the inner loop — capture, categorise, format, publish, validate.

Here’s what surprised me: automating the inner loop didn’t just save time. It changed what i chose to work on. When capturing and processing are essentially free, you stop filtering so aggressively at the front door. I read more broadly now — obscure newsletters, niche research, things i would have skipped in 2023 because the cost of processing them was too high. I didn’t expect that. I thought the whole point was doing the same things faster.

A prediction

Three years ago i ended with some predictions. I said Notion would IPO as one of the most valuable companies in the world (it hasn’t, and i’ve since left the platform). I said AI would have profound impacts on the future of work (this one landed, rather emphatically). I said large businesses would need to get more agile with IT procurement (they’re trying, slowly).

Here’s my updated prediction. Within two years, some version of this system — a personal knowledge base of plain files, orchestrated by AI agents, with automated capture and processing — will be standard for anyone doing serious information work. For regulated industries, shared corporate environments, or anyone whose data is too sensitive to feed through AI, the path is less clear. But the direction is set. Open data platforms have the structural advantage.

Most corporations are behind. That’s understandable — procurement, risk, and governance move slowly. But at the individual level, there is very little excuse. Obsidian is free. The AI tokens cost less than a coffee habit. Start there.

As Bill Gurley put it: “We evolve with our tools. You wouldn’t run a high production farm without a tractor. You wouldn’t do it with a plow and oxen. If you’re worried about this, the best thing you can do is run at it.”

The inner loop gets faster every month. The outer loop is where the value lives.

Useful links

The tools

- Obsidian – Free, local-first knowledge base. Your notes are plain markdown files on your hard drive.

- Obsidian CLI – Official command-line interface for scripting and automation.

- Obsidian Web Clipper – Browser extension for saving articles directly into your vault.

- Claude Code – Anthropic’s terminal-based AI agent. Free with a Claude Pro subscription.

The ideas

- File over app – Steph Ango’s essay on why the files you create are more important than the tools you use to create them.

- Claude Code Skills – Anthropic’s public repository of example skills, including the document creation skills that power Claude’s built-in capabilities.

Making videos about this

- Artem Zhutov – Daily workflows using Claude Code as a personal AI operating system inside Obsidian.