The Idea Maze

Before building, map the space: the key forks, dead ends and dependencies—so you can choose a promising path and run smarter tests.

Author

Chris Dixon (2013; building on Balaji S. Srinivasan’s “Startup Engineering” lectures)

Model type

Before building, map the space: the key forks, dead ends and dependencies—so you can choose a promising path and run smarter tests.

Chris Dixon (2013; building on Balaji S. Srinivasan’s “Startup Engineering” lectures)

Chris Dixon’s Idea Maze frames startup/product creation as navigating a maze of choices—technology, business model, go-to-market, timing, regulation, and more. Great founders study prior attempts, imagine how the maze might shift, and plan sequence and wedge entry points before running experiments. Use it as a thinking tool to reduce naive detours, not as a crystal ball.

Map dimensions – tech approach, target segment, price model, distribution, data/standards, complements, regulation. Each creates forks.

Sequence matters – decide build order (what must precede what), entry wedge, and triggers that open new corridors (platform shifts, cost curves).

Study prior art – list who tried what, why they failed/succeeded, and what has changed (devices, bandwidth, APIs, costs).

Choose corridors, not points – prepare 2–3 plausible routes with pre-defined switch rules if facts contradict assumptions.

Probe, don’t pontificate – run cheap tests to validate corridor assumptions; update the map as reality pushes back.

Zero-to-one product/venture ideation.

Entering regulated or multi-sided markets (payments, health, marketplaces).

Major pivots where distribution or complements change the viable path.

Technical strategy when platform or cost curves are in flux (AI, edge, new standards).

Define the mission & constraints – problem, target user, must-haves, guardrails (runway, compliance).

List forks per dimension – e.g., self-serve vs sales-led, SDK vs SaaS, centralised vs on-device, regulated vs unregulated niches.

Study the maze – 10+ historical attempts; note why now (what walls moved: tech, policy, behaviour). Add likely incumbent responses.

Draw 2–3 corridors – each with a wedge (the smallest use case you can dominate), build order, and distribution plan.

Write falsifiable assumptions per corridor – critical uncertainties, success metrics, kill/switch thresholds.

Run probes – smallest tests that hit the riskiest assumptions (design partnerships, fake doors, concierge pilots).

Update the map – double down on corridors that clear thresholds; prune dead ends; log learnings for new entrants.

Revisit on regime shifts – new platforms, cost drops, or rule changes can open hidden doors; remap quarterly.

Retrospective coherence – the maze can look obvious only after success; treat it as a planning aid, not prophecy. (Critiques: execution and effectual, improvisational learning often dominate.)

Over-planning – months mapping, little learning; bias to short probes.

Ignoring distribution – great tech in a corridor with no repeatable channel.

False “why now” – hype without a real wall moving (cost/UX/regulation).

Single-path dogma – lock-in to one corridor; keep alternates with pre-set switch rules.

Click below to learn other mental models

Before building, map the space: the key forks, dead ends and dependencies—so you can choose a promising path and run smarter tests.

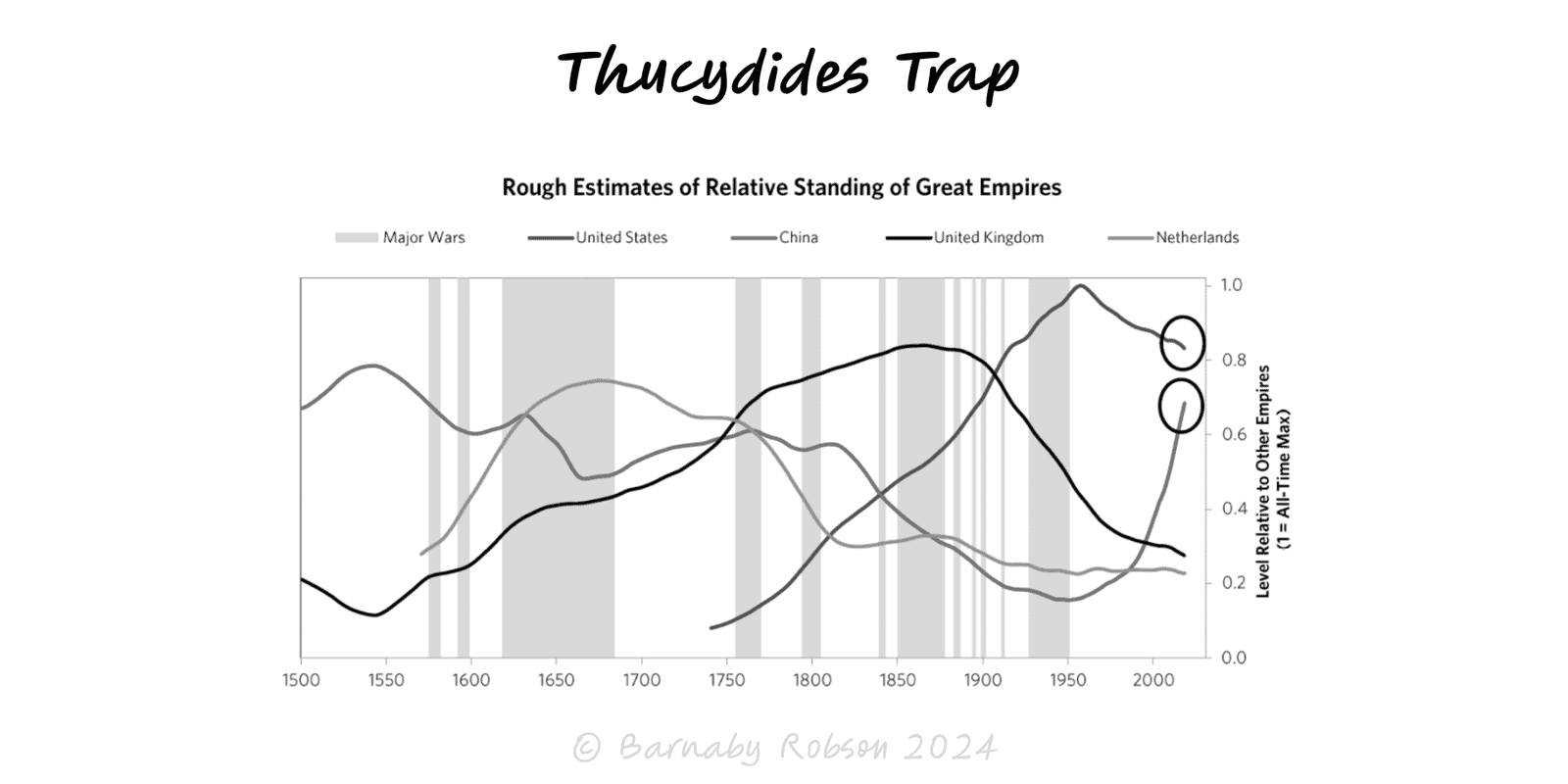

When a rising power threatens to displace a ruling power, fear and miscalculation can tip competition into conflict unless incentives and guardrails are redesigned.

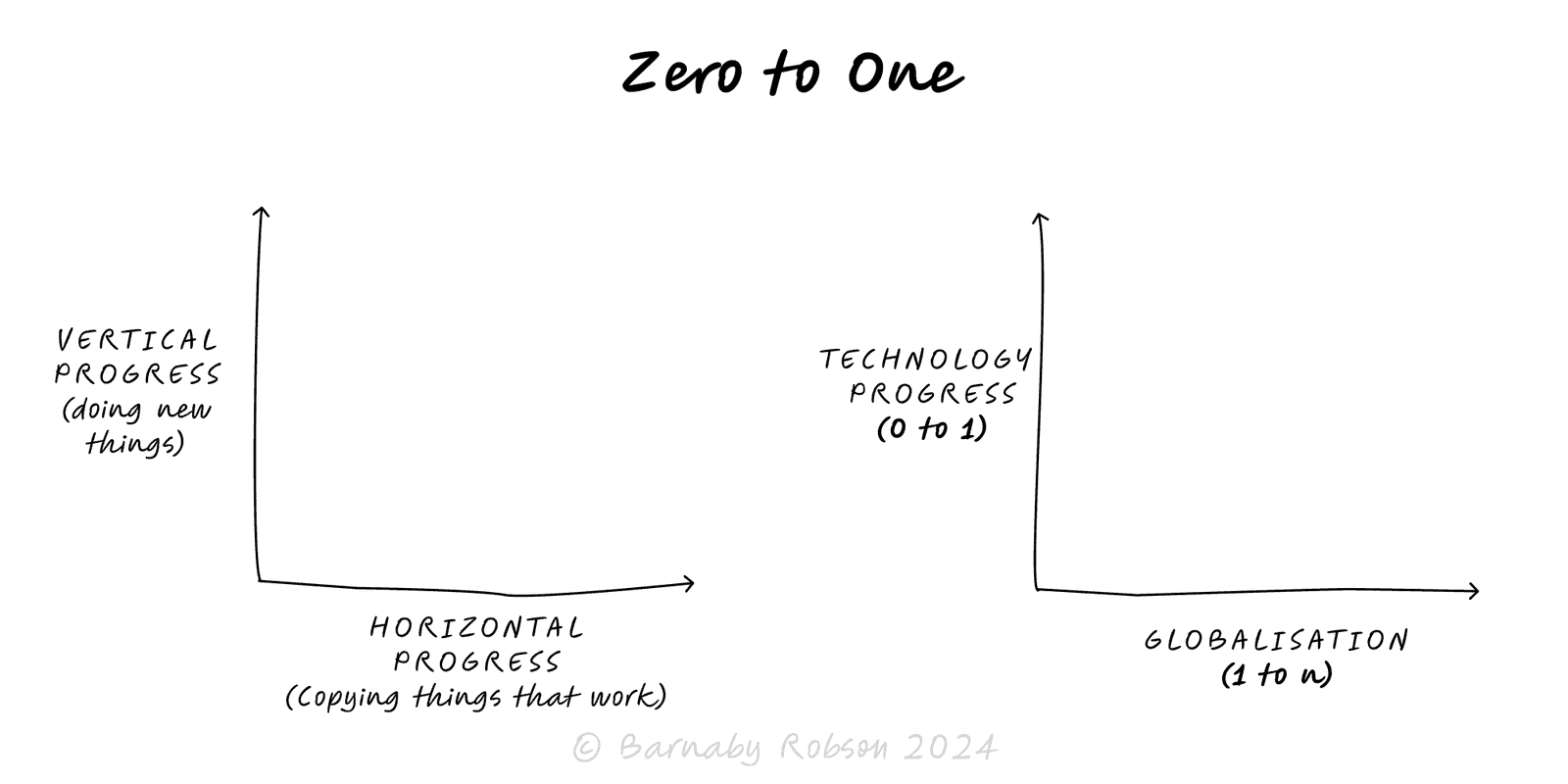

Aim for vertical progress—create something truly new (0 → 1), not just more of the same (1 → n). Win by building a monopoly on a focused niche and compounding from there.