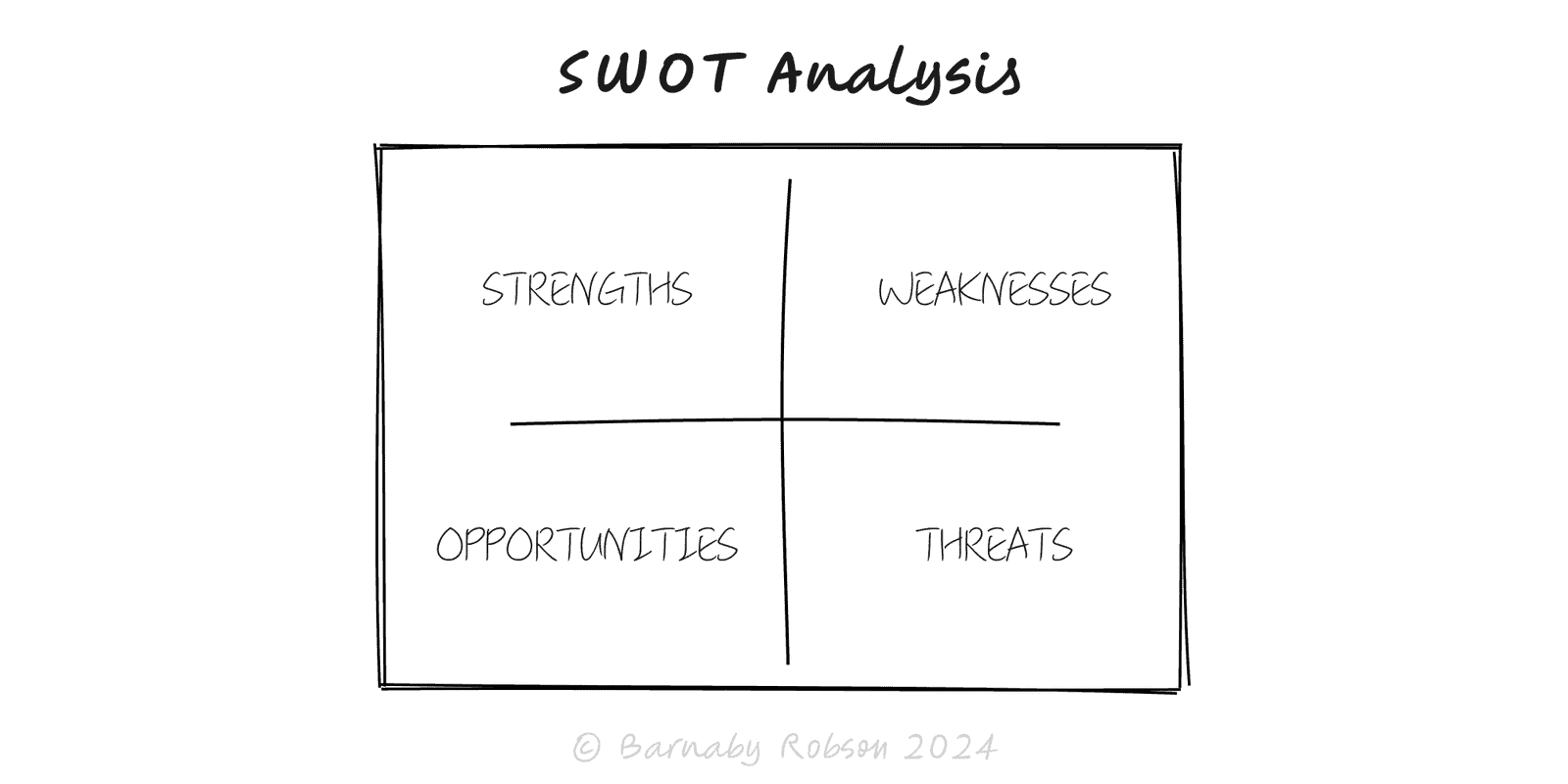

SWOT Analysis

Map internal factors (Strengths, Weaknesses) and external factors (Opportunities, Threats), then convert the grid into a short list of strategic moves.

Author

Albert Humphrey (popular attribution from 1960s–70s planning practice); later formalised with TOWS by Heinz Weihrich

Model type