Occam’s Razor

When multiple explanations fit the evidence, prefer the one with the fewest necessary assumptions.

Author

William of Ockham

Model type

When multiple explanations fit the evidence, prefer the one with the fewest necessary assumptions.

William of Ockham

Attributed to the 14th-century philosopher William of Ockham, and originally stated as “do not multiply entities beyond necessity.” When several explanations fit the facts, prefer the simplest that still explains the data.

Competing hypotheses: list explanations that account for the same facts.

Parsimony test: rank by assumptions/complexity (entities, parameters, ad hoc fixes).

Evidence first: only choose the simpler option if predictive adequacy is comparable.

Update: if residuals or new data expose gaps, add warranted complexity.

Root-cause analysis: avoid multi-factor just-so stories when one mechanism fits observed failures.

Model selection: analytics and forecasting; penalise complexity (AIC/BIC/MDL) to reduce overfitting.

Commercial narratives: diligence storylines and board papers—pick the leanest hypothesis consistent with facts.

Product/design: ship the minimal viable mechanism; defer optionality until validated.

Process and policy: streamline rules—remove steps that lack demonstrable risk reduction.

Define the question and enumerate plausible hypotheses.

State assumptions for each; note data requirements and implied mechanisms.

Test predictive adequacy on current evidence; reject underperformers.

Prefer the simplest remaining (fewest assumptions/parameters) that passes tests.

Monitor for anomalies; add complexity only to explain persistent residuals.

Simplest isn’t always true: prefer evidence over elegance.

Ambiguous “simplicity”: depends on description language; use explicit penalties (e.g. AIC/BIC) where possible.

Premature closure: don’t ignore hidden variables or non-linear interactions when data support them.

Overfitting by subtraction: oversimplified models can miss tail risks and regime changes.

Click below to learn other mental models

Before building, map the space: the key forks, dead ends and dependencies—so you can choose a promising path and run smarter tests.

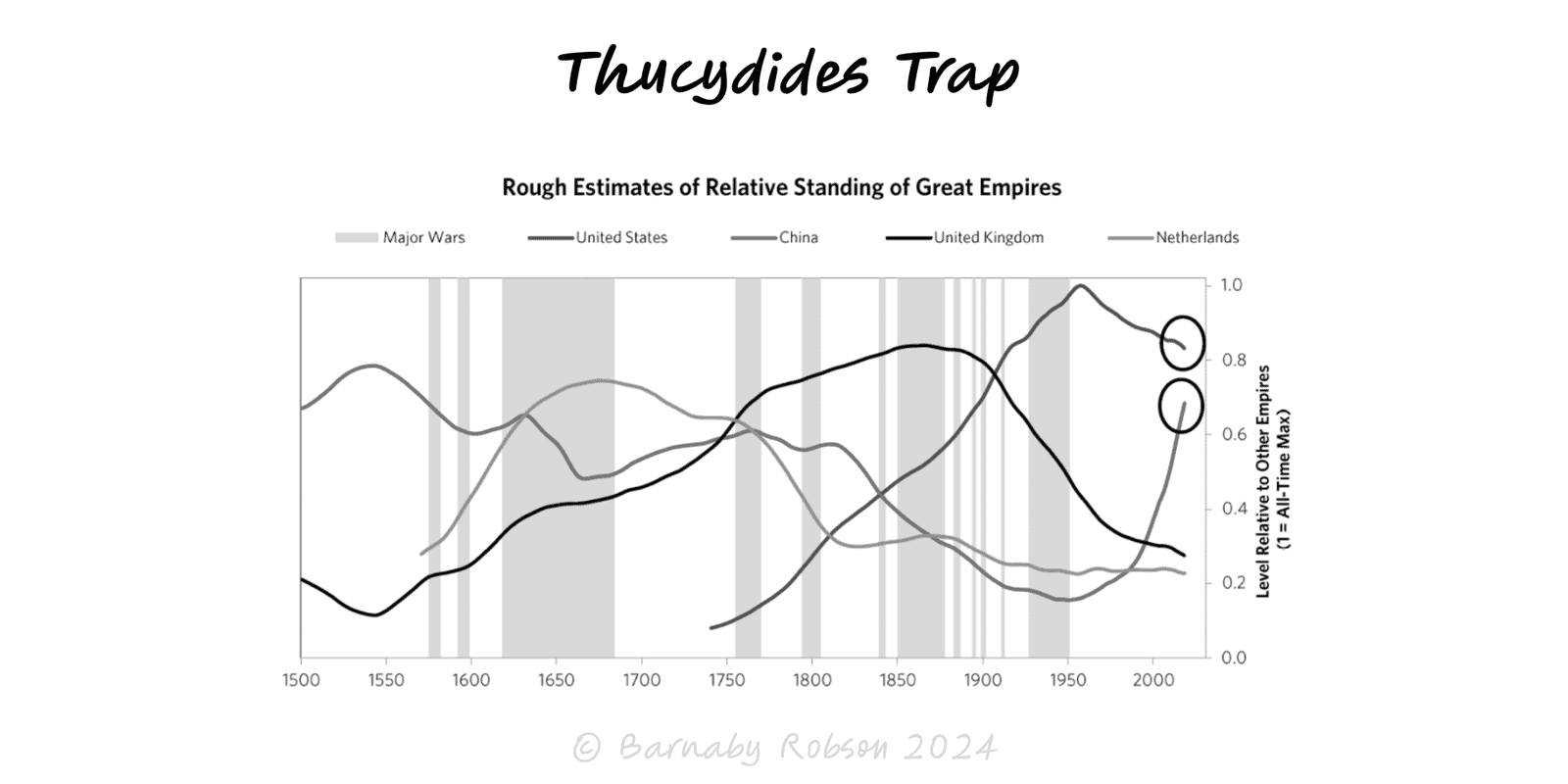

When a rising power threatens to displace a ruling power, fear and miscalculation can tip competition into conflict unless incentives and guardrails are redesigned.

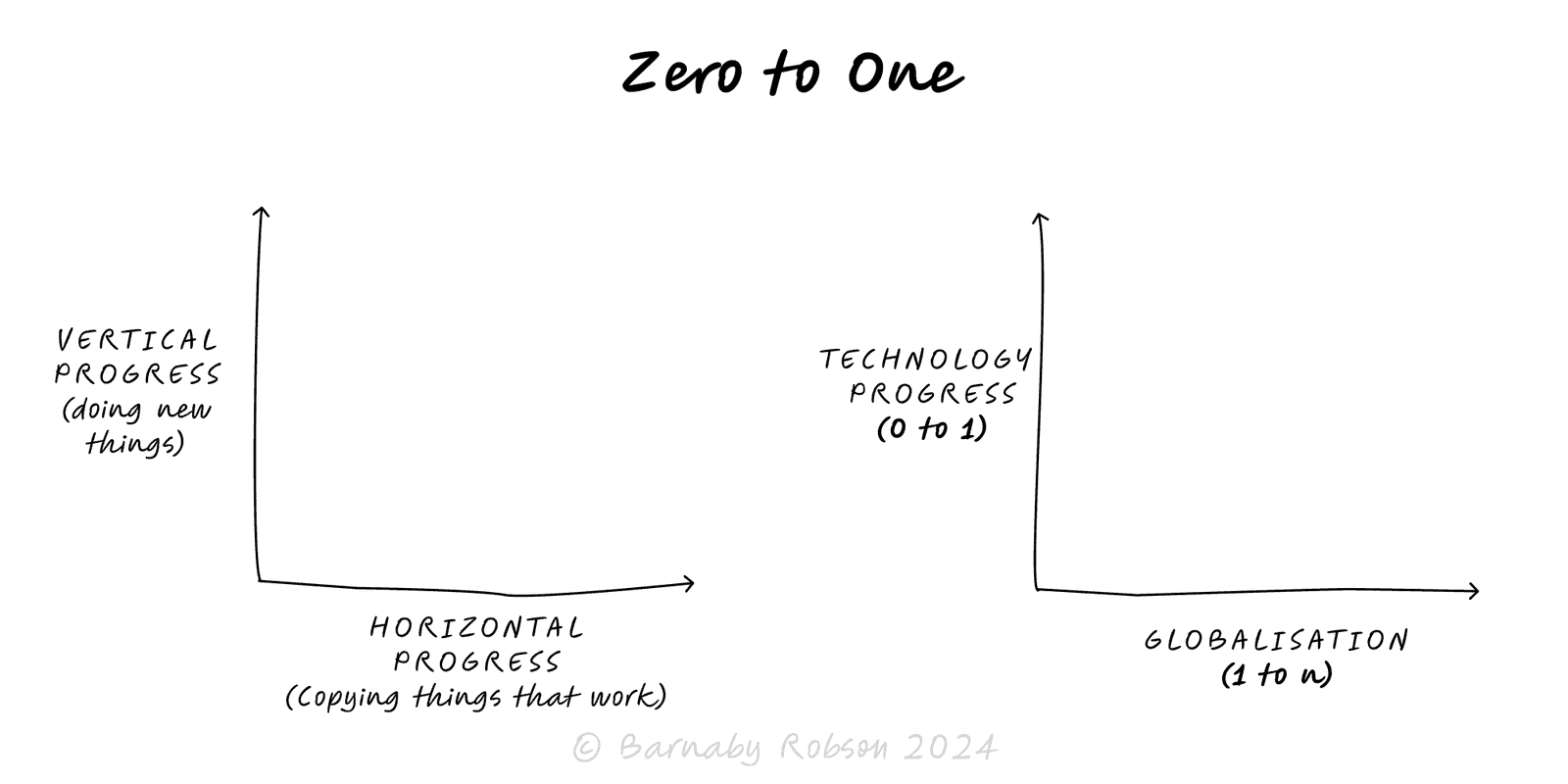

Aim for vertical progress—create something truly new (0 → 1), not just more of the same (1 → n). Win by building a monopoly on a focused niche and compounding from there.