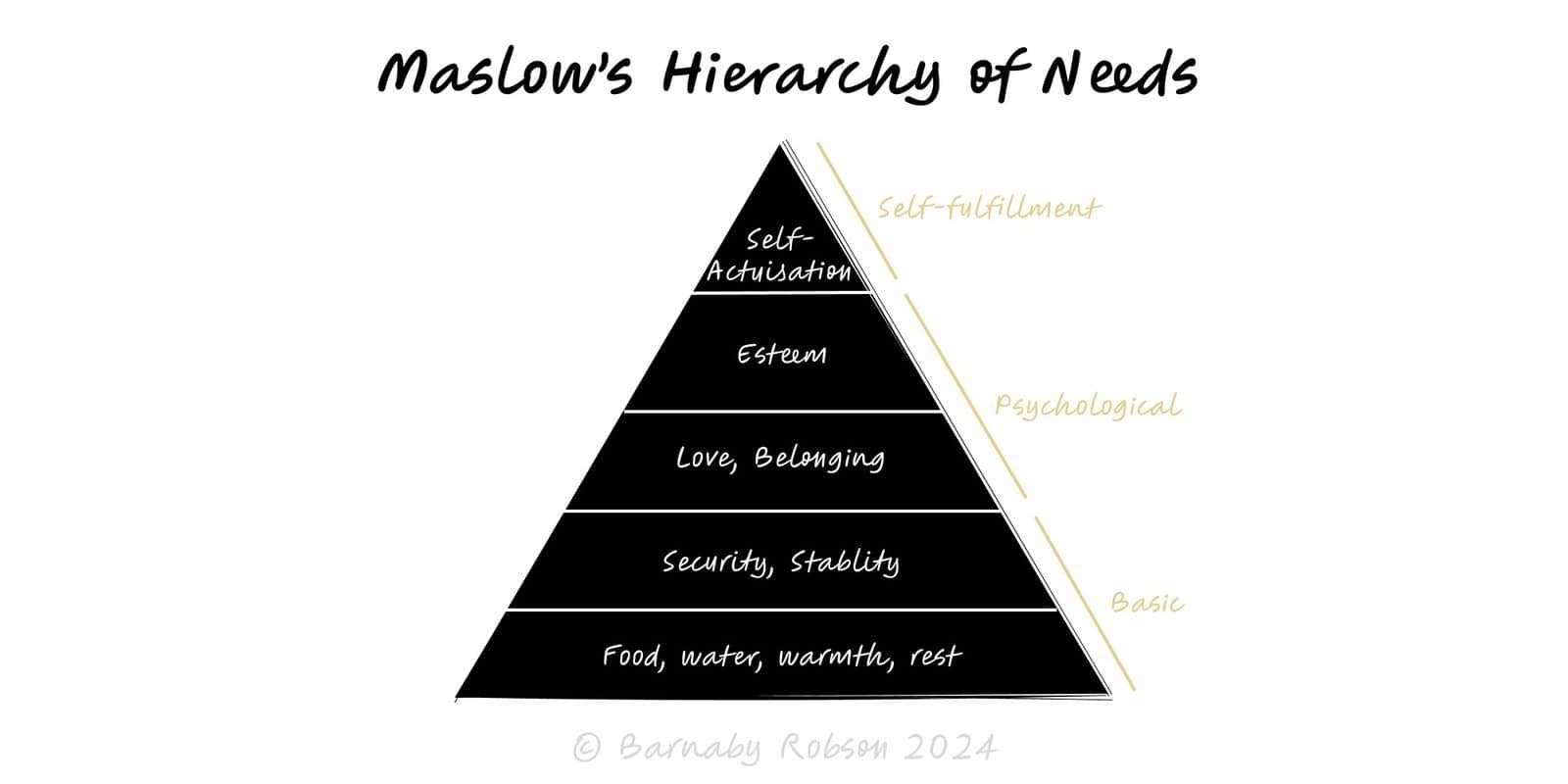

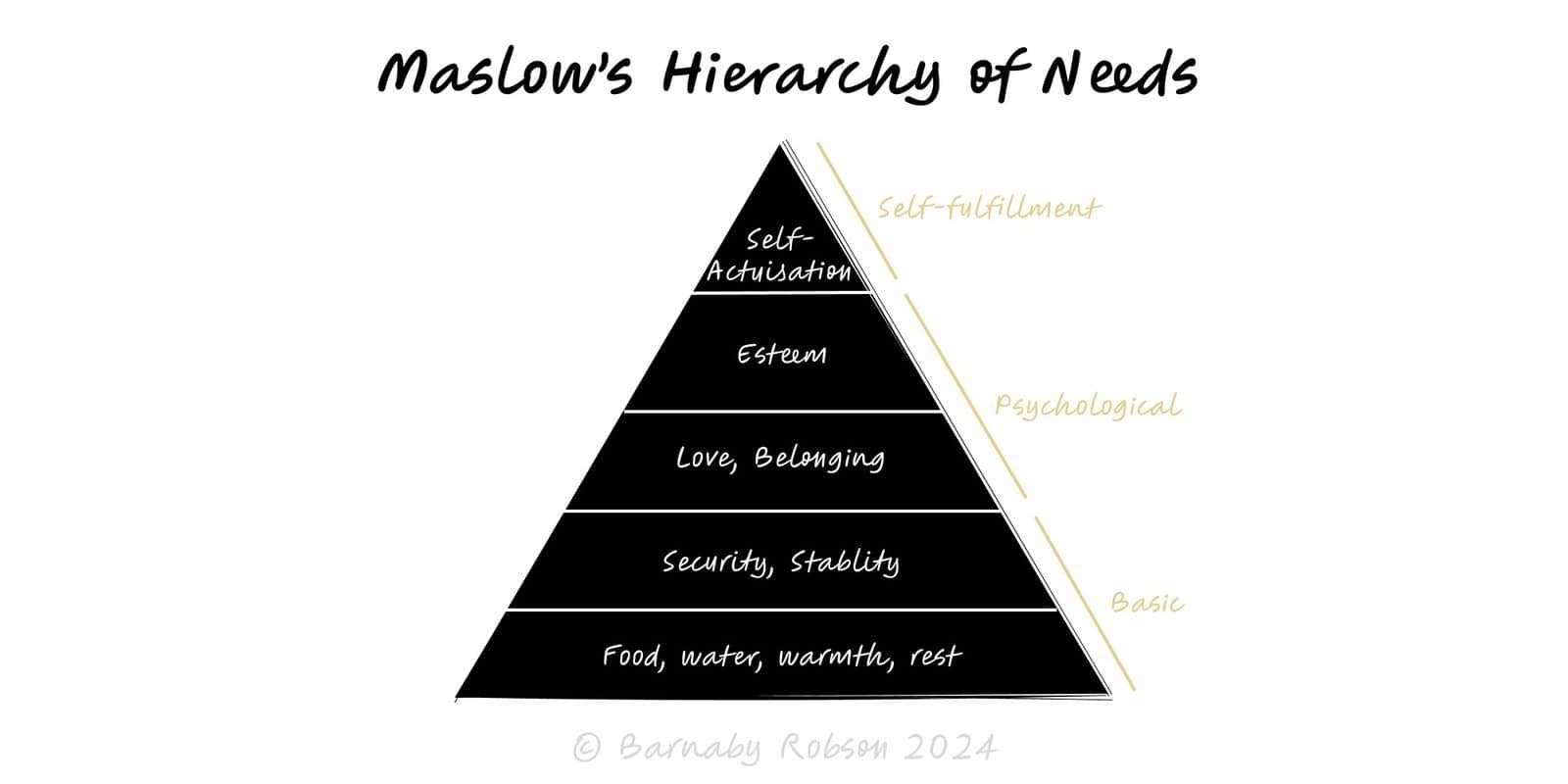

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

A motivation heuristic: people prioritise unmet lower-order needs before higher ones. Use it to diagnose constraints and design incentives.

Author

Abraham H. Maslow

Model type

A motivation heuristic: people prioritise unmet lower-order needs before higher ones. Use it to diagnose constraints and design incentives.

Abraham H. Maslow

Proposed in 1943 and developed through the 1950s, Maslow argued that human motivation reflects layers of needs. Lower levels are more pressing when unmet; multiple levels can operate at once.

Physiological – basic survival: rest, food, health.

Safety – security, income stability, predictable rules.

Belonging – affiliation, team inclusion, community.

Esteem – status, mastery, recognition, autonomy.

Self-actualisation – realising potential, purpose, creativity. (Some add “self-transcendence” as a further tier.)

Employee experience – sequence interventions: fair pay and safety → team belonging → growth and autonomy.

Change management – reduce safety threats first before appealing to mission.

Product/service design – position offers by the lowest unmet need they solve.

Customer segmentation – craft messages by segment need-state rather than demographics.

Education and L&D – preconditions for learning: psychological safety, belonging, then stretch goals.

Define the cohort (employees, users, customers) and context.

Diagnose unmet needs via surveys, behaviour, and constraint mapping.

Act on the lowest unmet need first; remove frictions before aspiration messaging.

Instrument outcomes (retention, productivity, NPS, activation) and iterate up the stack.

Personalise where feasible; individuals sit at different levels.

Rigid ladder fallacy – levels can overlap; people may pursue esteem or purpose despite insecurity.

Cultural variance – weighting of needs differs across contexts.

Vagueness in measurement – tie each need to observable proxies.

Ignoring constraints – motivation fails if basic frictions (pay, safety, time) persist.

Click below to learn other mental models

Before building, map the space: the key forks, dead ends and dependencies—so you can choose a promising path and run smarter tests.

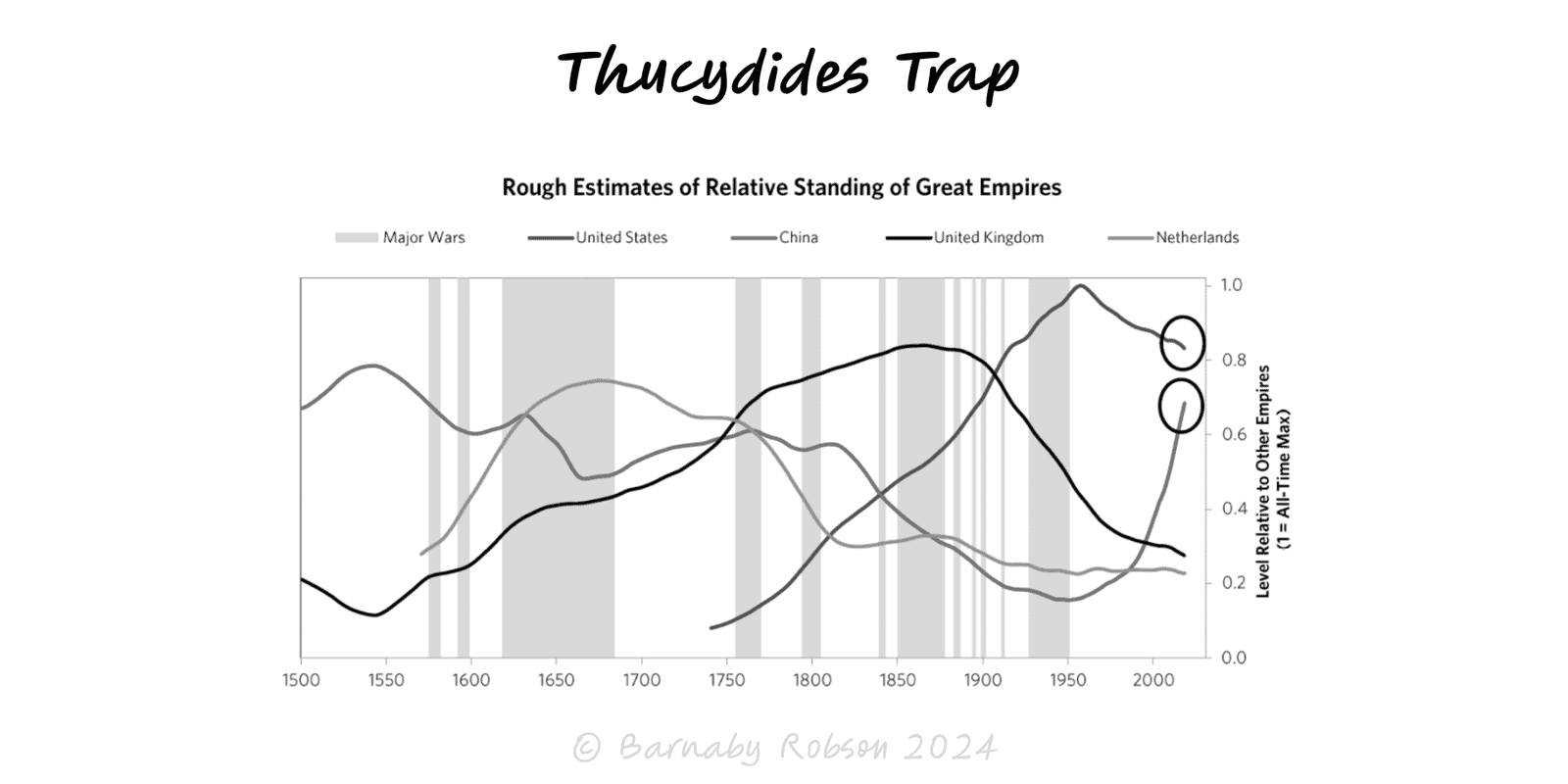

When a rising power threatens to displace a ruling power, fear and miscalculation can tip competition into conflict unless incentives and guardrails are redesigned.

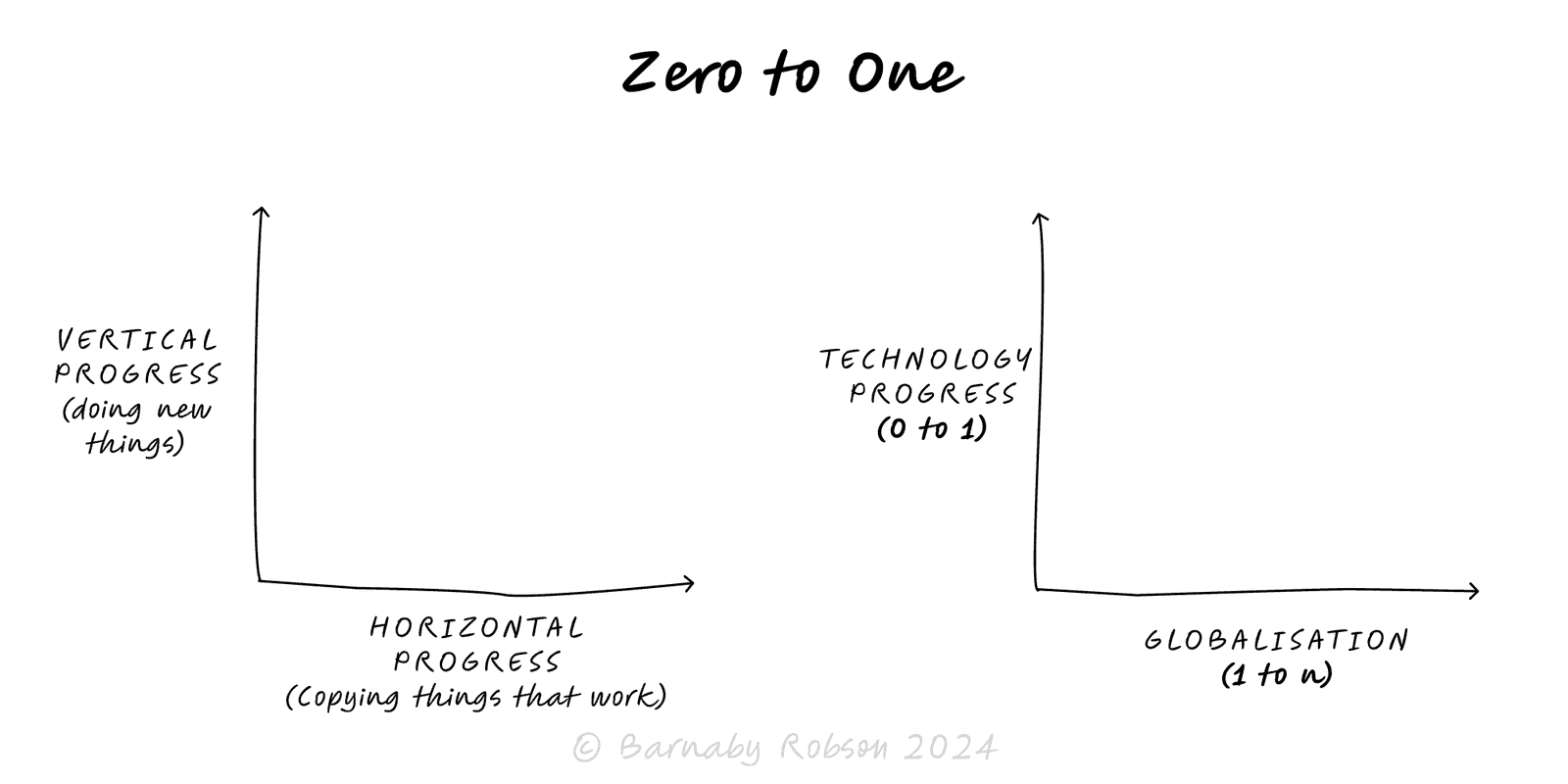

Aim for vertical progress—create something truly new (0 → 1), not just more of the same (1 → n). Win by building a monopoly on a focused niche and compounding from there.