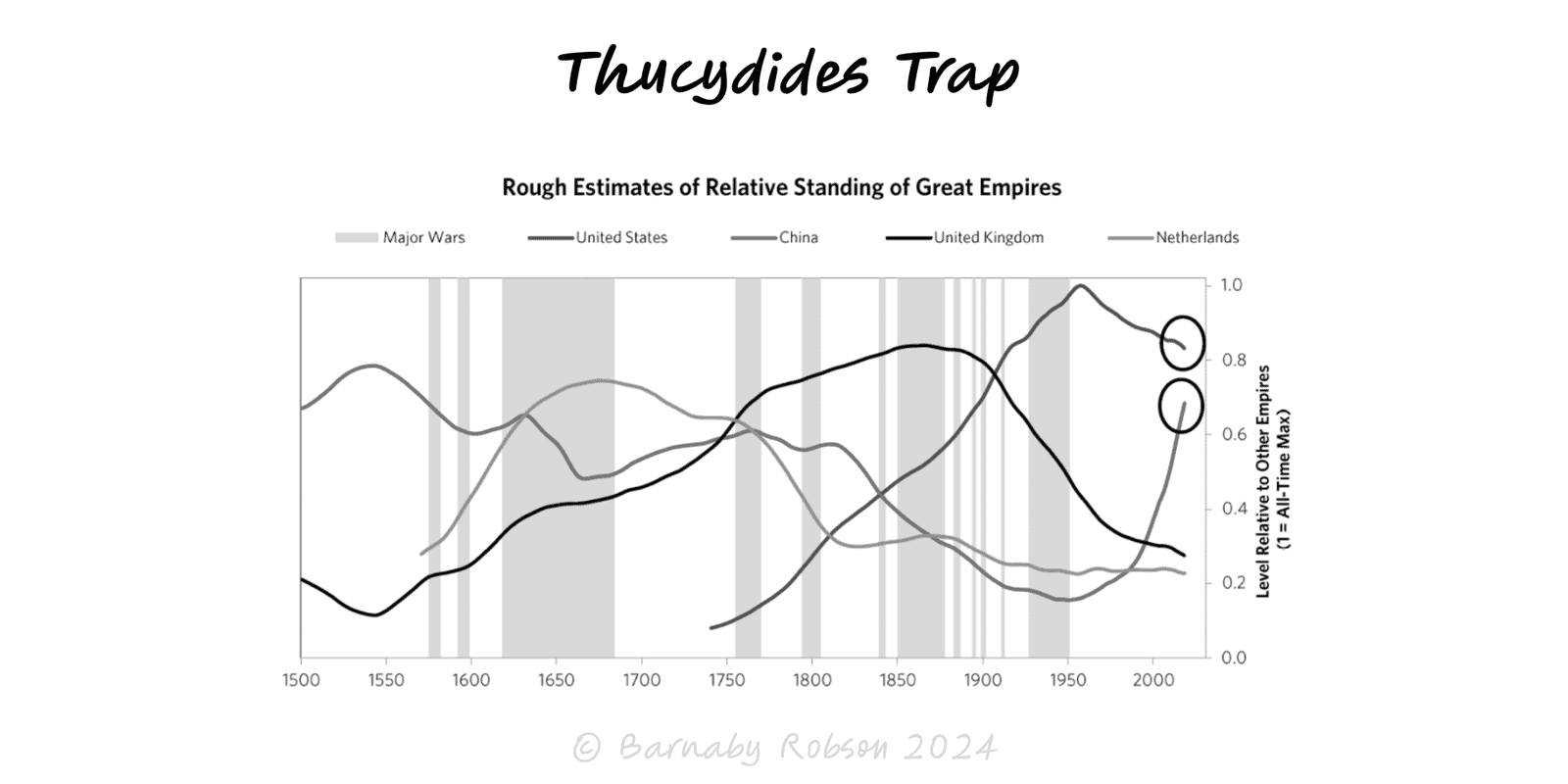

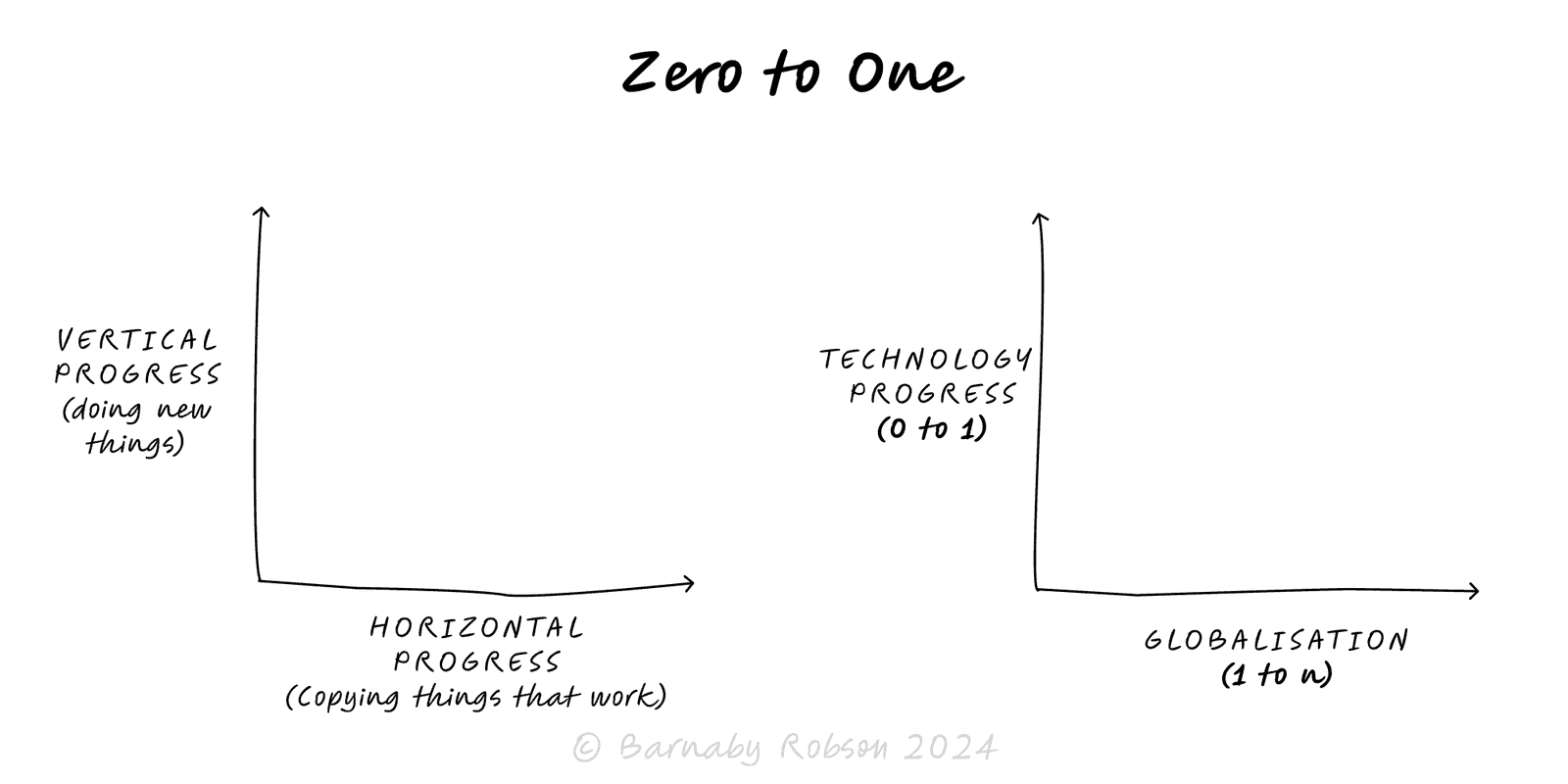

Game type – zero-sum (one’s gain is another’s loss) vs non-zero-sum (scope for win–win or traps).

Information – complete/incomplete; perfect/imperfect; simultaneous vs sequential moves.

Equilibria – Nash (no unilateral gain by deviating), subgame perfect (credible in every subtree), mixed strategies when no pure equilibrium exists.

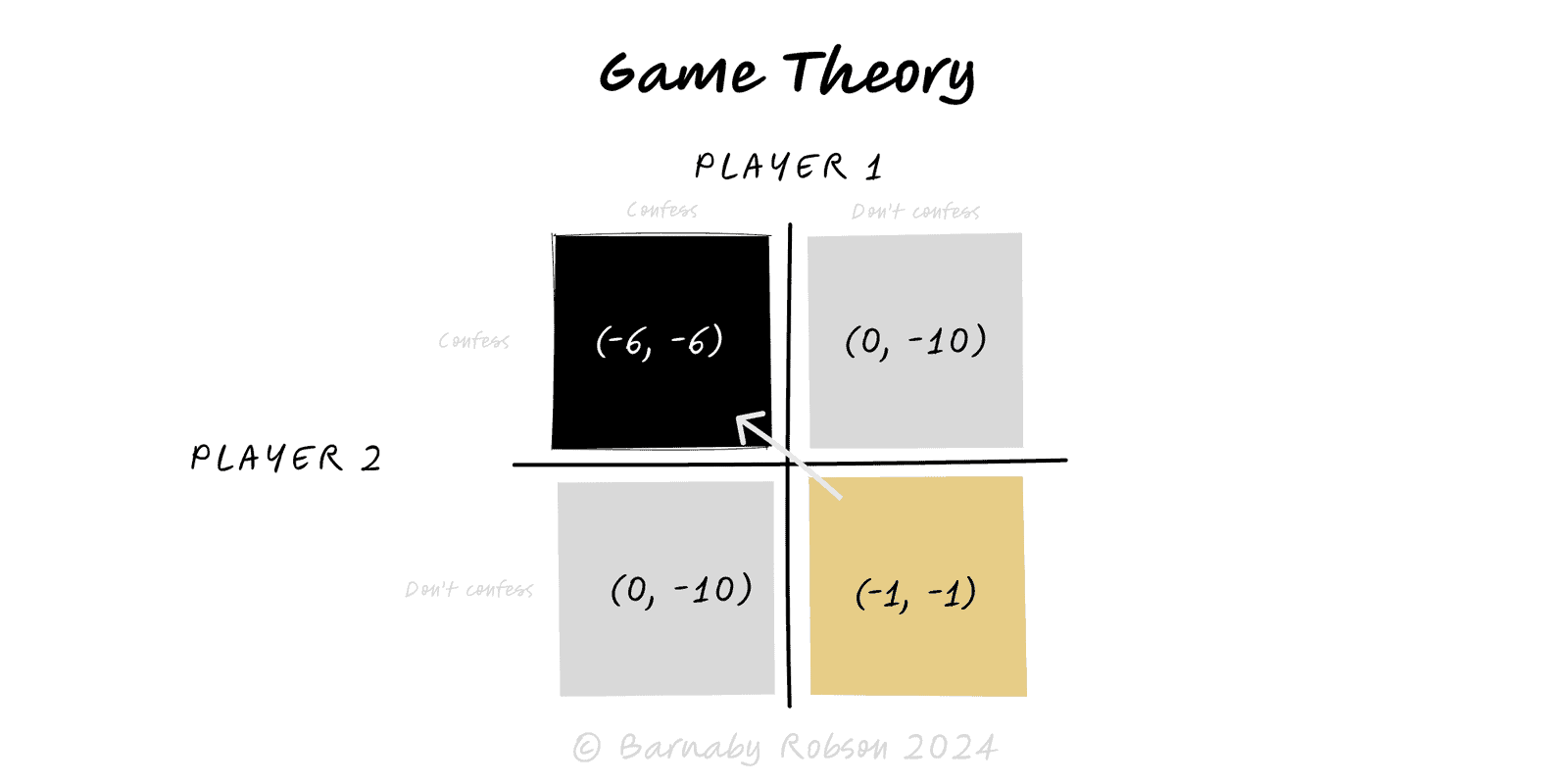

Canonical games – Prisoner’s Dilemma (co-operation trap), Stag Hunt (coordination & trust), Battle of the Sexes (coordination with preference conflict), Matching Pennies (zero-sum).

Dynamic effects – repeated games enable reputation, reciprocity, and trigger strategies; signalling/screening convey or extract private information; commitment and credible threats reshape incentives.

Mechanism design – set rules/contracts/auctions so participants’ incentives produce the outcome you want.