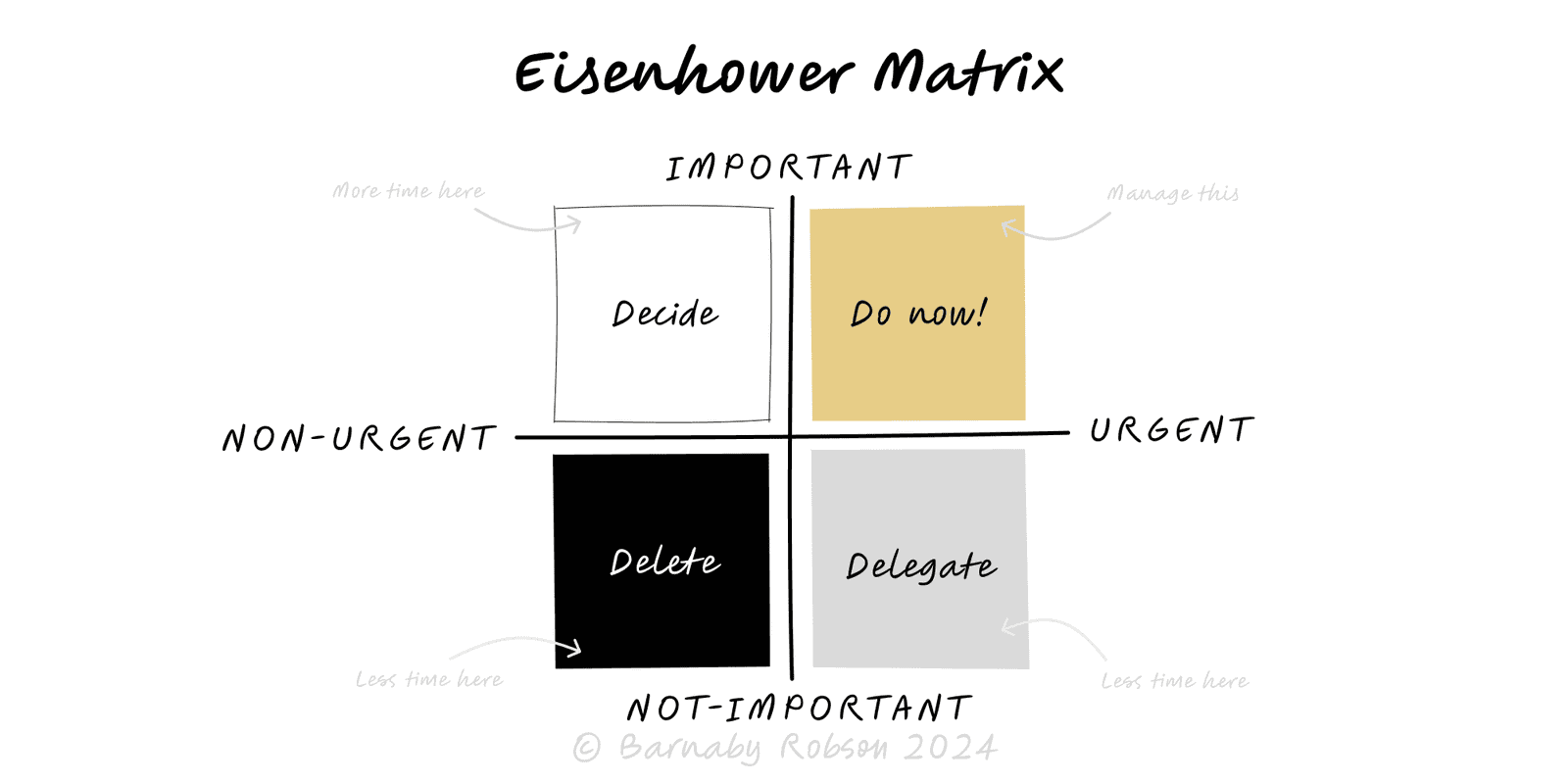

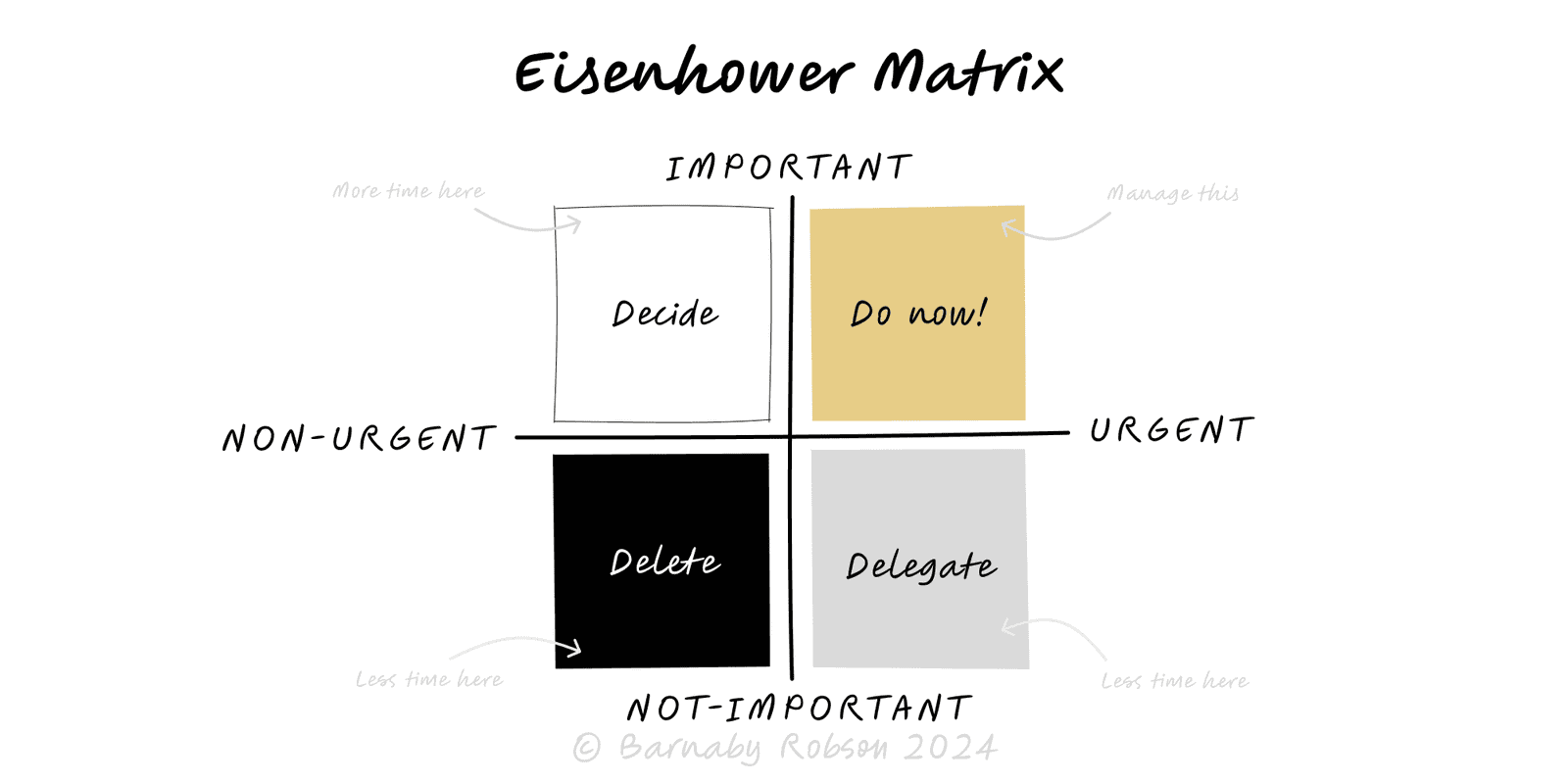

Eisenhower Matrix

Prioritise by importance, not urgency: Do, Schedule, Delegate, or Eliminate.

Author

Dwight D. Eisenhower (popularised by Stephen R. Covey)

Model type

Prioritise by importance, not urgency: Do, Schedule, Delegate, or Eliminate.

Dwight D. Eisenhower (popularised by Stephen R. Covey)

The Eisenhower Matrix sorts work by two variables: Importance (does it advance the goal?) and Urgency (does it require immediate attention?). Urgency grabs attention; importance creates results. By classifying tasks into four quadrants and applying a default action to each, you protect time for what matters and stop busywork from dominating.

Axis definitions

Quadrants and default actions

Personal and team weekly planning.

Incident and support triage.

Backlog grooming and sprint hygiene.

Meeting audits and inbox discipline.

State outcomes – write this week’s top 3 objectives; define “important” against them.

List tasks – dump everything; include meetings and recurring work.

Classify – label each item Q1–Q4 quickly; don’t overthink.

Allocate time

Q1: timebox today; create buffers for known spikes.

Q2: block calendar time; protect 2–4 hours of deep work most days.

Q3: delegate, decline, or convert to async; add rules (office hours, templates).

Q4: delete or set a small cap (e.g., 15 minutes at day end).

Engineer fewer Q1s – add prevention tasks (Q2) that reduce recurring fires.

Review cadence – daily 10-minute sweep; weekly reset with a fresh matrix.

Undefined “important” – without explicit goals, everything looks urgent; write OKRs or weekly outcomes first.

Urgency addiction – the adrenaline of Q1/Q3 crowds out Q2; protect deep work with hard calendar blocks.

Fake urgency – others’ poor planning becomes your emergency; use SLAs and escalation rules.

Over-granularity – classifying micro-tasks wastes time; group by workstreams.

Delegation theatre – dumping without context boomerangs; delegate outcomes, not chores.

Neglecting recovery – no slack means more Q1; schedule buffers.

Click below to learn other mental models

Before building, map the space: the key forks, dead ends and dependencies—so you can choose a promising path and run smarter tests.

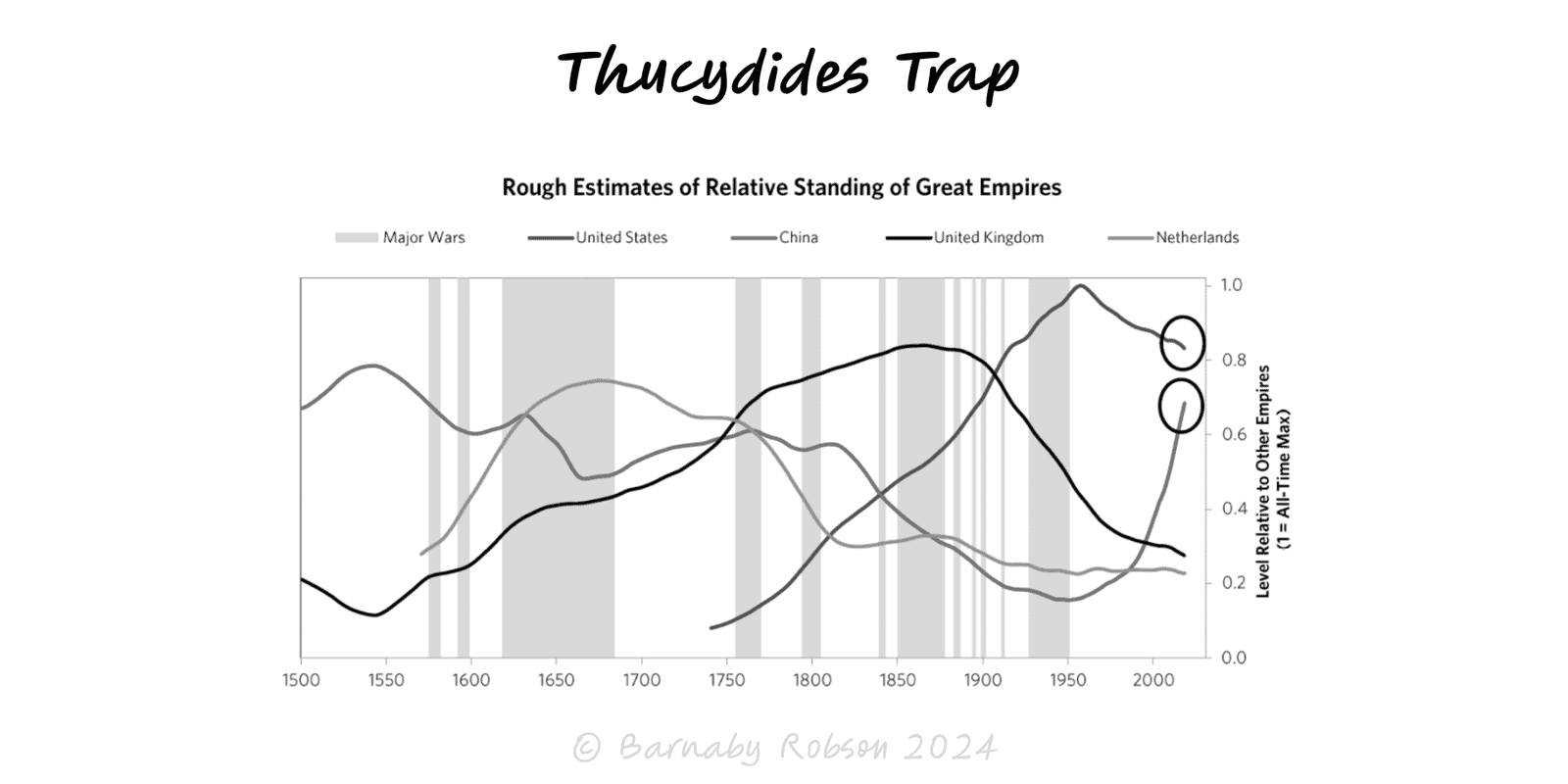

When a rising power threatens to displace a ruling power, fear and miscalculation can tip competition into conflict unless incentives and guardrails are redesigned.

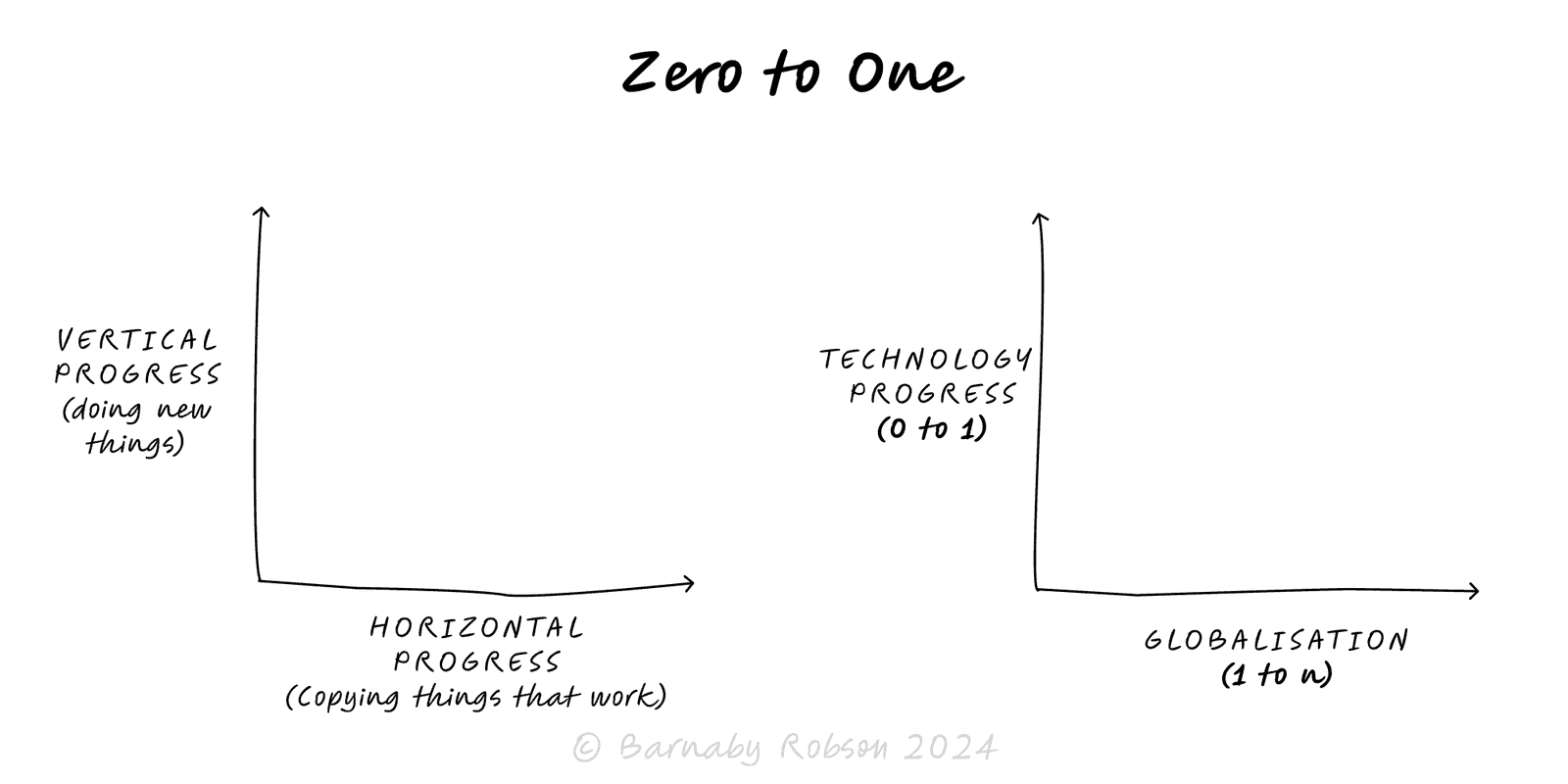

Aim for vertical progress—create something truly new (0 → 1), not just more of the same (1 → n). Win by building a monopoly on a focused niche and compounding from there.