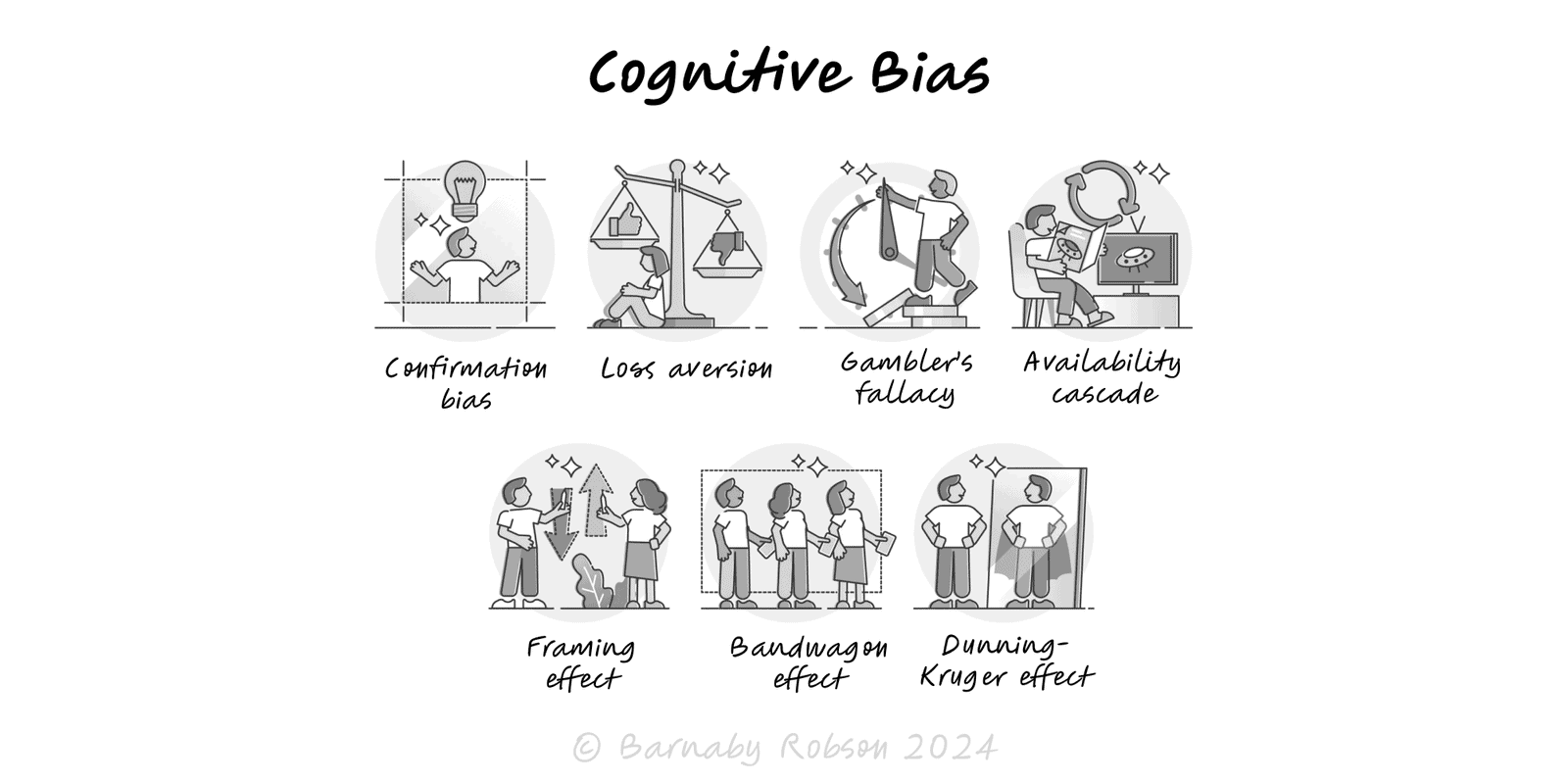

Cognitive Bias

Systematic shortcuts in thinking that create predictable errors. Know the patterns; design decisions and communication to counter their effects.

Author

Behavioural economics and cognitive psychology (notably Daniel Kahneman & Amos Tversky)

Model type