This was my first visit to the United States, at the age of forty-five – a fact that caused people’s eyes to pop out of their heads with such regularity that I began to suspect they thought I was a wanted criminal. But the thought that kept surfacing, from Los Angeles to Orlando to San Francisco and back, was that America is essentially England – wider, louder, more expensive, and with better weather, but recognisably the same civilisation with the volume turned up and the safety nets removed. The language is the same. The cultural assumptions – individualism, property rights, the conviction that effort should be rewarded – are the same. What differs is the scale, the ambition, and the price tag.

Start with expense, because it colours everything. A Japanese lunch for three in San Francisco: five hundred dollars. A three-star Michelin tasting menu at Atelier Crenn courtesy of my generous friend Ryan: an eyewateringly large sum, but the kind of once-in-a-lifetime experience that justifies itself precisely because you would never do it twice. The food was exceptional – inventive, beautifully composed, the kind of cooking that makes you reconsider what a vegetable is capable of. The only quibble was the narration: every course arrived with a soliloquy about the provenance of the ingredients, the philosophy of the chef, the emotional journey of the wine pairing. The food needed no explanation; it was the explanations that needed editing. The tipping culture compounds the assault: every transaction ends with a screen swivelled towards you, its preset options starting at eighteen per cent and climbing with the quiet menace of a protection racket. The trick, I found, is to stop thinking of tips as optional generosity and start treating them as a compulsory service charge – which, in economic terms, they are. The mental tax diminishes once you stop pretending you have a choice.

The visible bedrock of this service economy is Latino. They clean the hotels, sweep the streets, drive the taxis, bus the tables, and pour the coffee. In Orlando, the taxi driver from the airport spoke no English at all – not a word. America is a nation built by immigrants, and the energy of each new wave has always been the fuel in the engine. The issue – and it is impossible to spend a week in California without confronting it – is not immigration itself but the collapse of any serious control over it. San Francisco is the case study in what happens when permissive policy meets reality: a city where you must think carefully about which street to walk down, which route to drive, because a wrong turn deposits you in what can only be described as an open-air asylum. The “Fuck ICE” graffiti and transgender flags remain ubiquitous – this is still the beating heart of woke America – but the gap between the ideology and the squalor it has produced is now too wide for even its most committed defenders to ignore with a straight face.

Orlando itself has the faintly exhausted charm of a city that exists primarily to entertain other people’s children. The airport carries a whiff of the 1980s – not unpleasantly, but noticeably, like a shopping centre that peaked during the Reagan administration. Domestic air travel is frequent and accessible – security queues move fast, people fly with their pets, and at baggage claim anyone can walk up to the carousel without barriers or checks, which would give a European security official a seizure. But the product itself lags well behind Asia. I paid handsomely for a six-hour business class from Orlando to San Francisco on United, only to discover that the seat did not recline. Not partially, not inadequately – it simply did not recline at all. A business class seat on a six-hour flight, bolt upright, at a premium fare. On Cathay Pacific or Singapore Airlines you would be horizontal with a duvet and a glass of champagne. Worse still, a United business class ticket does not include lounge access – you must pay extra for the privilege of sitting in a room with free coffee before boarding the plane on which you will not be reclining. The whole arrangement has the feel of an airline that has decided its customers have nowhere else to go, which on domestic routes is largely true.

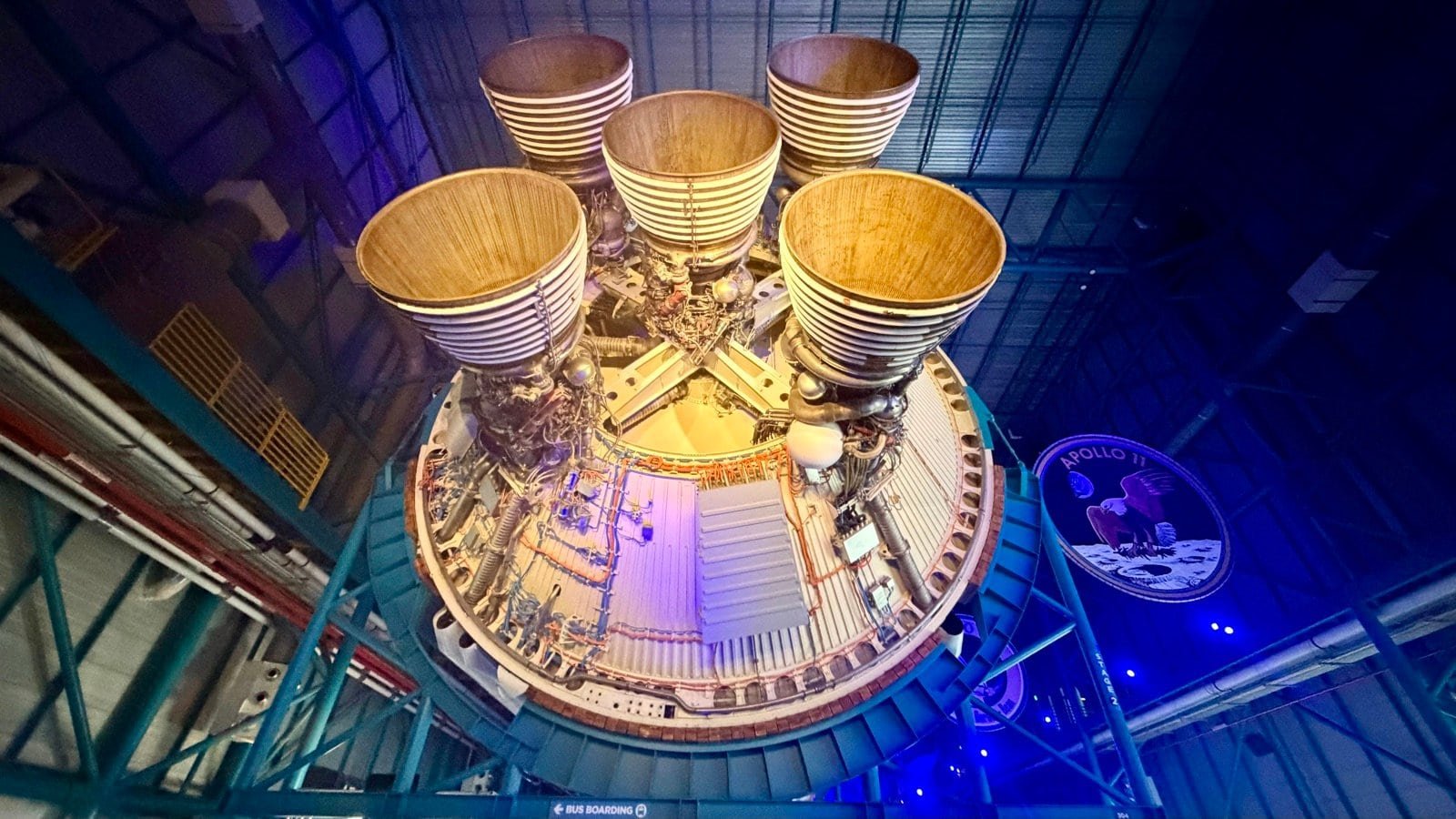

A highlight was NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, and specifically a memo that has stayed with me. In 1961, an engineer named John C. Houbolt – convinced that Lunar-Orbit Rendezvous was the only viable way to reach the moon, and frustrated that nobody in the hierarchy would listen – bypassed every layer of management and wrote directly to Robert Seamans, NASA’s associate administrator. Nine pages, beginning with “Somewhat as a voice in the wilderness…” and building to the blunt question: “Do we want to get to the moon or not?” It was a career-ending move that didn’t end his career. By the following summer, NASA had adopted his method, saving an estimated twenty billion dollars and making Apollo 11 possible. There is something very American about that story – the impatience with process, the preference for decision over deliberation, the assumption that the only real question is whether you have the nerve.

Touring the Kennedy Space center, you can see the launch sites of NASA, SpaceX, and Blue Origin all lined up along the coast – three eras of American ambition sitting side by side, the government programme that started it, the private ventures that are continuing it, and the Atlantic stretching out beyond them all. I met Don Thomas, an astronaut who was rejected by NASA three times before being accepted on his fourth application in 1990 – after moving to Houston, earning his pilot’s licence, and simply refusing to take no for an answer. He went on to fly four shuttle missions. When I asked what surprised him most about space, he said it was not the darkness or the weightlessness but the overwhelming beauty of the Earth – how thin and fragile the atmosphere looked from above, how vivid the colours were, how impossible it was to take your eyes off the planet you had just left. And the biggest shock on returning? His wife asked him to take the rubbish out. He said he wouldn’t have it any other way. The space programme, for all its bureaucratic bloat, remains one of the few human enterprises that makes you feel the species might be worth the trouble.

San Francisco is where these contradictions are sharpest. I arrived at one in the morning and drove through the Tenderloin, which resembled nothing so much as the opening scene of a zombie film: bodies slumped in doorways, figures lurching across intersections, the unmistakable choreography of fentanyl. This is not a neighbourhood you stumble into by accident; it is a neighbourhood you are warned about by your hotel, your taxi driver, and anyone who has spent more than a day in the city. The mental map one builds of San Francisco is defined as much by avoidance as by attraction – which blocks to skip, which parks to bypass after dark, which stretches of Market Street have tipped from edgy to dangerous. And yet twelve hours later, walking downhill from Nob Hill to Fisherman’s Wharf in brilliant sunshine – the streets so steep they feel like they were designed to test the commitment of pedestrians – the city was heartbreakingly beautiful – the bay glittering, Alcatraz brooding on its rock, the Golden Gate Bridge emerging like a propaganda poster for the American Dream. Drinks at the Top of the Mark with my wife and friend Ryan as the sun set over the Pacific. Taking the old cable car back up to Nob Hill at the end of the day – clinging to the side, the city falling away behind you – was one of the pure pleasures of the trip. The range between the city’s worst and best, compressed into a single day, is wider than anything I have encountered in London or Hong Kong.

The tech-money atmosphere is unmistakable but curiously unstylish. People are dressed as if comfort were a moral imperative and appearance a bourgeois distraction. Hoodies and trainers at restaurants charging five hundred dollars a head. It is genuinely difficult to distinguish a billionaire from a graduate student, which is either admirably democratic or an aesthetic catastrophe, depending on your sympathies. The explanation, I think, is that San Francisco is a city of new money – and new money, unlike old money, has not yet learned that taste is a form of communication. In London, you can read someone’s class from their shoes. Here, everyone wears the same shoes.

The drive through Silicon Valley with Ryan was a pilgrimage of sorts. Stanford’s campus is absurdly vast – more country estate than university. We spotted Brad Gerstner in the morning, wearing his trademark red sunglasses, radiating the quiet confidence of a man whose portfolio is performing. Apple Park, Nvidia, Google – the campuses sit along the highway like temples to a religion whose god is quarterly earnings. Sand Hill Road and Menlo Park – names I had thought about for years, read about in countless articles – turned out to be modest, suburban, almost anticlimactic. The epicentre of global venture capital looks like a dentist’s office park in Surrey. But the ecosystem is real: Stanford pumps talent into the machine, the machine generates wealth, the wealth funds the next generation, and within minutes of all of it you have hiking trails, beaches, and lakes. If you can afford the entry price – and increasingly, few can – the quality of life is extraordinary.

What genuinely startled me was seeing Waymo vehicles navigating city streets with no human at the wheel. I had read about autonomous vehicles; seeing one pull up, empty, unlock its doors, and drive away is something else entirely. It felt like stepping into the future, the way the first smartphone must have felt to someone used to a landline. A Cybertruck rolled past shortly afterwards, angular and absurd, looking like a tank designed by a child with access to sheet metal and no adult supervision. Between the self-driving taxis and the stainless-steel trucks, San Francisco’s streets felt like a technology expo that had escaped its convention centre.

The roads, however, are not great. Potholes, cracked asphalt, faded markings – nothing catastrophic, but a persistent shabbiness that makes China’s immaculate highways feel like a rebuke from a more attentive civilisation. The contrast is instructive: America can put autonomous vehicles on roads it cannot be bothered to resurface. The innovation happens at the top; the infrastructure quietly deteriorates at the base. American drivers, meanwhile, have a baffling attachment to the overtaking lane regardless of speed – cruising along clear highways at ten miles below the limit in the fast lane as if it were a scenic viewpoint. I have never done so much undertaking in my life, nor felt so justified in doing it.

Big Sur and Route 1 offered relief from urban contradictions. The drive south from San Francisco is quietly beautiful – half-forgotten coastal towns, vineyards, the Pacific crashing against cliffs. The most stunning stretch begins south of Carmel-by-the-Sea, where the road clings to the mountainside and the views open up like a block buster BBC nature documentary. The 17-Mile Drive through Pebble Beach is a manicured prelude – golf courses and cypress trees arranged with the precision of a Japanese garden.

A night among the redwoods at Big Sur Lodge had a romance to it that I had not expected. Rain on the roof of the wooden cabin, the trees enormous and indifferent overhead, the feeling of being genuinely remote despite being three hours from one of the world’s richest cities. Route 1, however, had closed overnight due to a mudslide – no protective netting, no concrete barriers, none of the engineering solutions that Hong Kong deploys against its own unstable hillsides – and we had to double back via the inland Route 101.

Santa Barbara was the California of my imagination: palm trees, blue skies, a relaxed warmth that felt cinematic in the best sense. I enjoyed it more than Los Angeles, which is damning with faint praise only because LA turned out to be more interesting than expected. The drive up to the Griffith Observatory passed through neighbourhoods that could have been transplanted from the nicer parts of London – Blackheath, Greenwich – with lawns and mature trees and the quiet self-assurance of money that has been there for a while. The observatory itself was freezing and rammed with tourists, but the views across the city were extraordinary: the Hollywood sign, the downtown towers, the endless grid of roads stretching to the horizon. Griffith J. Griffith himself – a Welshman who made his fortune in mining and gave the land to the city – embodies a particularly American story: immigrant makes good, gives back, name lives forever. It is a formula that still works, or at least still gets buildings named after you.

Hollywood Boulevard is the inevitable disappointment. Stars on the pavement, yes, but surrounded by McDonald’s and Madame Tussauds and the particular sadness of a place that trades entirely on its past. The international terminal at LAX, by contrast, was a pleasant surprise – modern, well-designed, with a Oneworld lounge that suggested someone, somewhere, had remembered that first impressions and last impressions are the ones that stick.

A few observations that resist tidy categorisation. The diversity of cars is striking: no single brand dominates the way Toyota owns Japan or BYD is conquering China. American pickup trucks are preposterously large – vehicles designed for a continent that has the space for them and the fuel subsidies to fill them. The absence of kettles in hotel rooms is a minor cultural outrage that reveals a deeper truth about a nation that has decided coffee is the only hot beverage worth making and has built an entire industry around this error. No toothbrushes or razors either – amenities that every Asian hotel provides as a matter of course – reflecting a culture that assumes you will bring your own or buy replacements at inflated prices from the lobby shop. The supermarkets, too, are a disappointment for anyone accustomed to Waitrose or M&S. The ready meal selection is sparse, the quality noticeably lower, and the general standard of packaged food would fails to compete with a Tesco or Sainsbury’s. For a country that prides itself on consumer choice, the grocery aisle is curiously underwhelming.

The size of people varies as dramatically as the landscape. Obesity tracks class with the same grim predictability as in Europe, though the American version is more extreme at both ends: the very fit are very fit, and the very large are very large. What is consistent across all sizes is a friendliness that can feel performative until you realise it isn’t – or at least, not entirely. People are genuinely more confident and outgoing than their British equivalents. Conversations start in lifts, in queues, in car parks. The emotional register is set several notches higher than the English default. Whether this is warmth or simply a culture that rewards extroversion is a question I will leave to the sociologists, though I note that the friendliness peaks immediately before and after tipping opportunities.

Having now visited China, India, and America within the space of a year, I find myself thinking about where these three powers stand in relation to each other – and about Dan Wang’s formulation in Breakneck that China is an engineering state and America a lawyerly one. The distinction is useful because it explains what you see on the ground. China builds: the roads are perfect, the factories hum, the infrastructure compounds on itself with the quiet relentlessness of an organism that has learned to metabolise investment into capability. America litigates: the high-speed rail approved by referendum in 2008 has produced more lawsuits than track, the roads are shabby, the airports lag behind Asia – and yet the country puts autonomous vehicles on streets it cannot be bothered to resurface. The innovation happens in spite of the system, not because of it.

India, I suspect, will not close the gap. It is a low-trust society with extraordinary individuals but no institutional machinery to coordinate them. The smartest Indians know this, which is why the best of them leave for Silicon Valley or Wall Street – becoming, in effect, America’s most reliable import. India’s contribution to the global order may ultimately be demographic and intellectual rather than industrial: a supplier of talent to the powers that can organise it, rather than a power that can organise itself.

Which leaves the question of whether the lawyerly state can outlast the engineering one. China builds bridges; America builds arguments about why the bridge cannot be built. China trains engineers; America trains lawyers to sue them. And yet – and this is the tension I cannot resolve – America remains the place where a NASA engineer can bypass the entire hierarchy with a nine-page memo and change the course of history, where an immigrant from Wales can give a city its most famous landmark, where a stranger will start a conversation in a car park for no reason other than friendliness. The system is creaking, the infrastructure is fraying, and the bill is always higher than you expected. But the nerve is still there. Whether nerve alone is enough is the question that will define the next decade. I left without an answer, and I suspect America doesn’t have one either.