Part 2 – 80/20 for Business

The 80/20 Business

Notes from Richard Koch’s ‘The 80/20 Principle’ on finding where you actually make money, focusing on the 20% of customers providing 80% of profit, and eliminating the rest.

MENU

Click the links below to see how 80/20 applies to each part of the business and operating model or simply scroll down to read the full article.

BUSINESS MODEL

›

Strategy & Profitability

Finding your core business

›

Marketing

Focusing on the 20% of customers providing 80% of profit

›

Selling

Directing sales efforts to the most profitable products and customers

OPERATING MODEL

›

Strategic simplification

Eliminating wasteful activities

›

Project management

Ensuring 20% of activities deliver 80% of project value

›

Decision making

Focusing on only a few crucial decisions

Read other parts of his series setting out the concepts from Richard Koch’s the 80/20 Principle:

Strategy & Profitability

The first question: Where are you *Actually* making money?

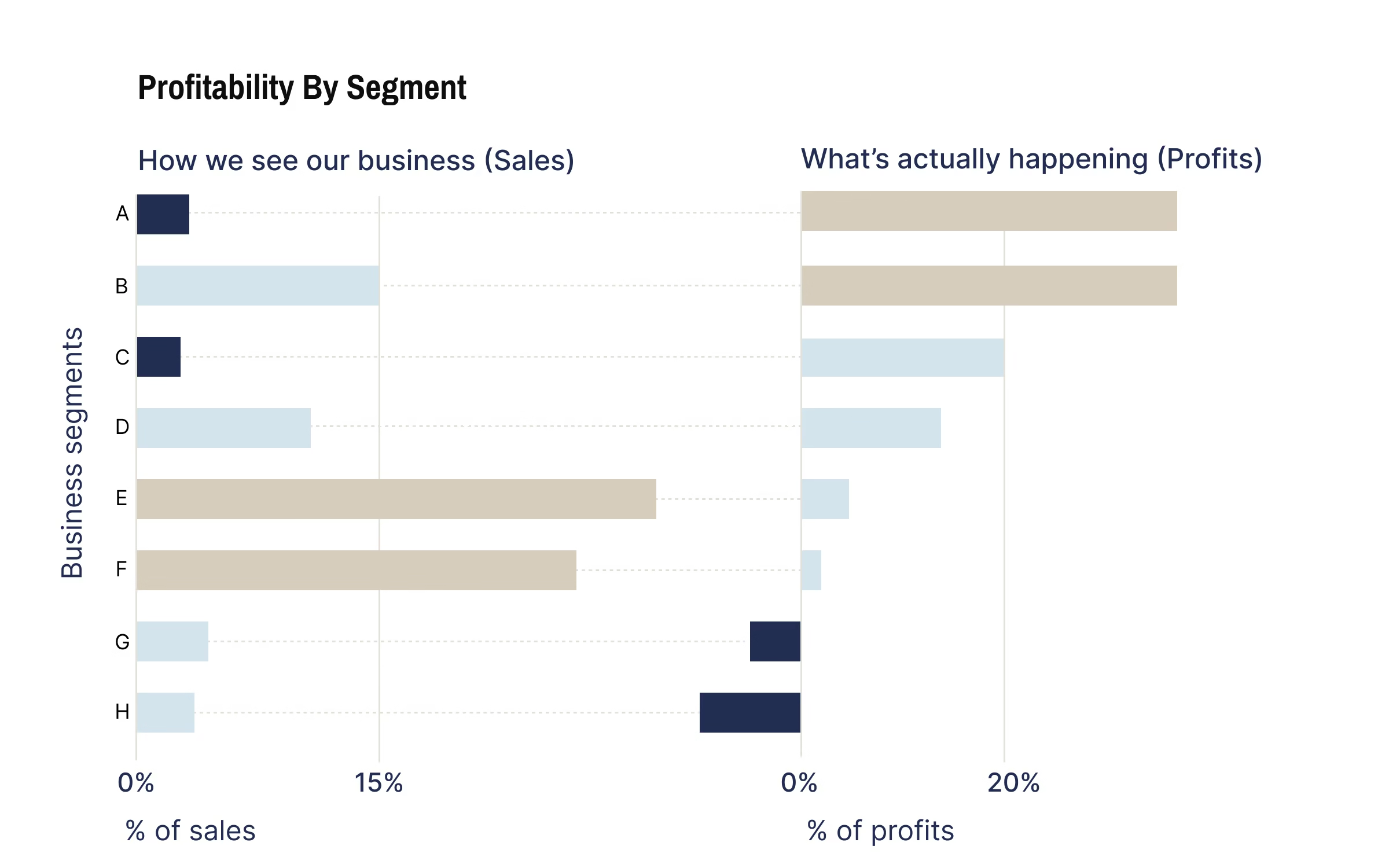

The problem with most business reporting: Most business are focussed on billings, GMV, revenues, etc. To understand your business, you must stop looking at revenue and start looking at profitability by segment. The results are rarely what you expect.

The problem with standard accounting: Standard cost systems make it near impossible to know true product profitability. This is because they often allocate overheads to business segments on a crude basis (e.g., percentage of revenue), hiding the true cost of certain high-maintenance products or services.

The 80/20 Diagnosis

Identify your segments: The first step to 80/20 Diagnosis is identify your business segments. A competitive segment is a part of your business where you face a different competitor or different competitive dynamics. Take any part of your business that comes to mind: a product, a customer, a product line sold to a customer type, or any other split that may be important to you (for example, consultants may think of M&A work). Now ask yourself two simple questions:

- Do you face a different main competitor in this part of your business compared to the rest of it? If the answer is yes, then that part of the business is a separate competitive segment (or simply segment for short).

- Do you and your competitor have the same ratio of sales or market share in the two areas, or are they relatively stronger in one area and you relatively stronger in another?

Understand true profitability: What you next have to do is to allocate all the overhead costs to each product group on some reasonable basis. The crudest way is to allocate costs on a percentage of revenues. A moment’s thought, however, should convince you that this will not be very accurate. Some products take a great deal of salespeople’s time relative to their value, for example, and others take very little. Some are heavily advertised and others not at all. Some require a lot of fussing around in manufacturing whereas others are straightforward. Take each category of overhead cost and allocate it to each product group on as accurate a basis as possible. Do this for all the costs, then look at the results.

80/20 Actions: Profits can be raised by a large degree by concentrating only on market and customer segments which are already the most profitable, and expanding them dramatically. The most profitable segments will tend to (but will not always) be where the firm enjoys the highest market shares, and where the firm has the most loyal customers (loyalty being defined by being longstanding and least likely to defect to competitors).

1. Identify segments

Split your business into competitive segments. A segment is any part of your business (a product, a customer type) where you face a different main competitor or different competitive dynamics.

2. Allocate *All* costs

Go beyond gross margin. Allocate every overhead cost-sales time, advertising, manufacturing complexity, R&D, administrative fuss—to each segment.

3. Visualise the truth

Visualise the Truth: You will inevitably find that 80% of your profits come from 20% of your segments. The rest are marginal, or actively losing you money.

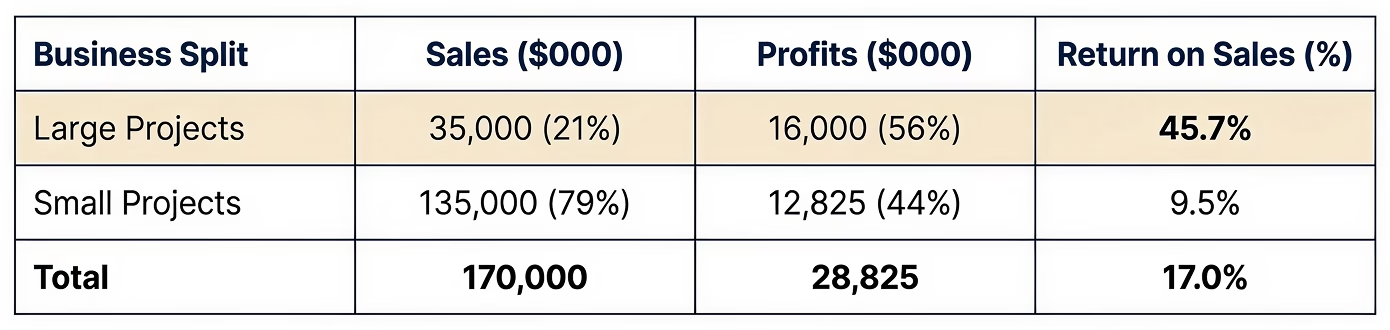

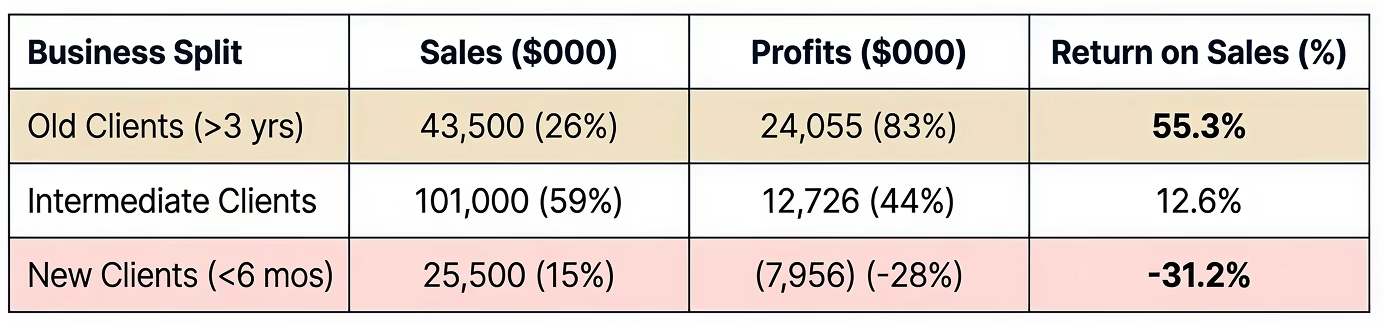

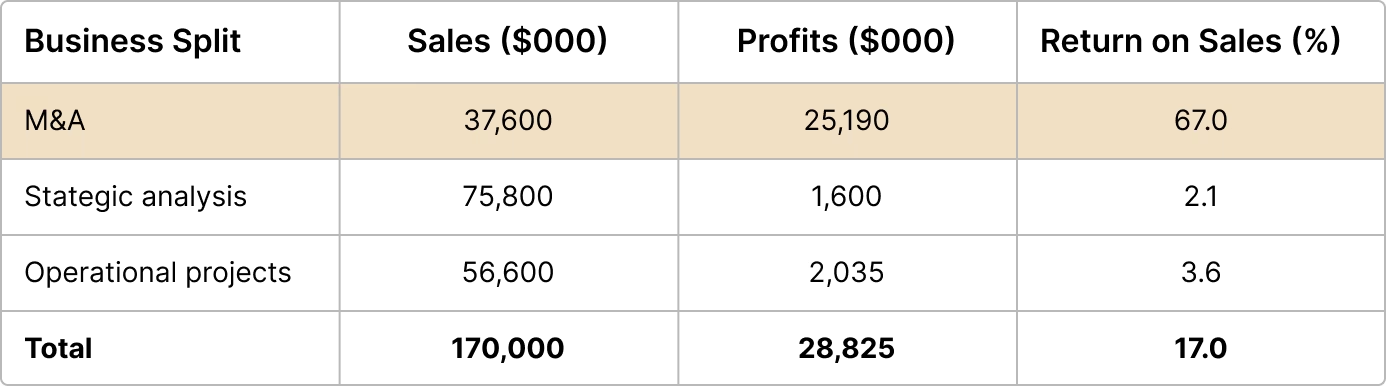

Case Study: 80/20 Analysis applied to a consulting firm

A strategy consulting firm with USD 170m of sales performed 80/20 analysis. They segmented their business two ways.

Notes from Barnaby:

- While it may have been the case for consulting that larger clients and projects were more profitable when Richard practiced consulting – my experience in the late 2020s is all consultants have raced to focus on the large Blue Chips – bidding each other down in that segment. Consequently it’s the middle markets deals and firms where margins tend to be higher.

- It’s certainly true that consulting margins are higher for Older / Established clients – IF they are loyal – due to the reduced ‘marketing costs’ (i.e. less time spent preparing fancy pitches etc).

Large v Small Projects

21%

Sales are large projects

56%

Profits are large projects

Key Insight: 56/21 rule. Large projects constitute only 21 percent of turnover but give 56 percent of profits. Revenue from small projects was a distraction, generating less than half the profit at a fraction of the margin. The real business was in large projects.

Old v New Clients – the hidden value of loyalty

26%

Sales are Old Clients

83%

Profits are Old Clients

Key Insight: 83/26 rule – The most loyal clients, representing just over a quarter of sales, delivered nearly all of the firm’s profits. New client acquisition was a money-losing activity. Need to strive above all to keep and expand long-serving clients who tend to be less price sensitive and can be served mostly cheaply.

By Project type

22%

Sales are M&A

87%

Profits are M&A

Key Insight: 22/87 rule. M&A work wildly profitable – generated 87% of the profits for 22 percent of the revenues. Efforts need to be redoubled to sell M&A work!

Profitability isn’t enough. Is it a good business?

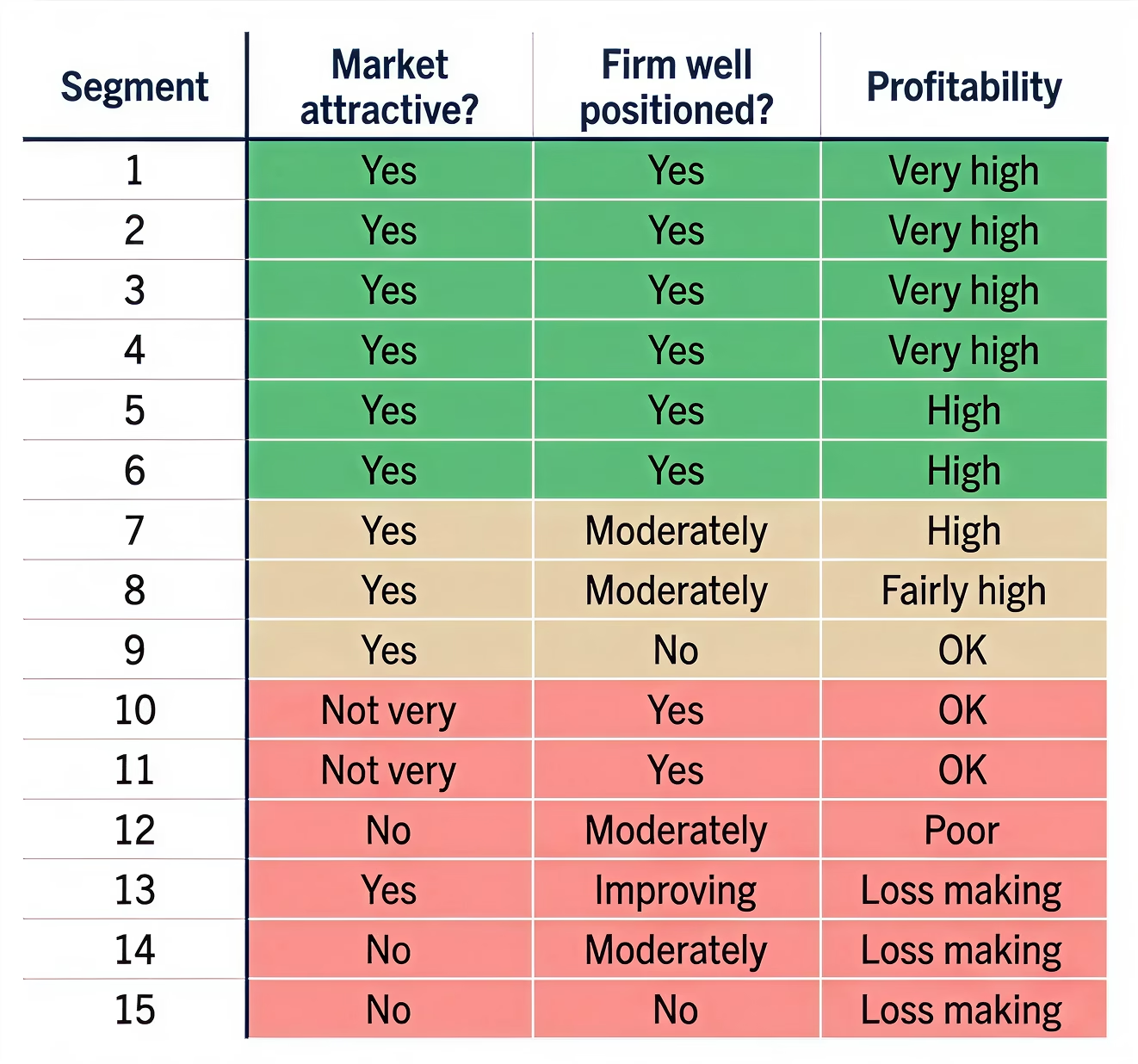

After identifying your profitable segments, ask two further questions:

Is the segment an attractive market to be in? (Growth, barriers to entry, bargaining power vs. customers & suppliers)

How well is our firm positioned in that segment? (Market share, unique capabilities, competitive strength)

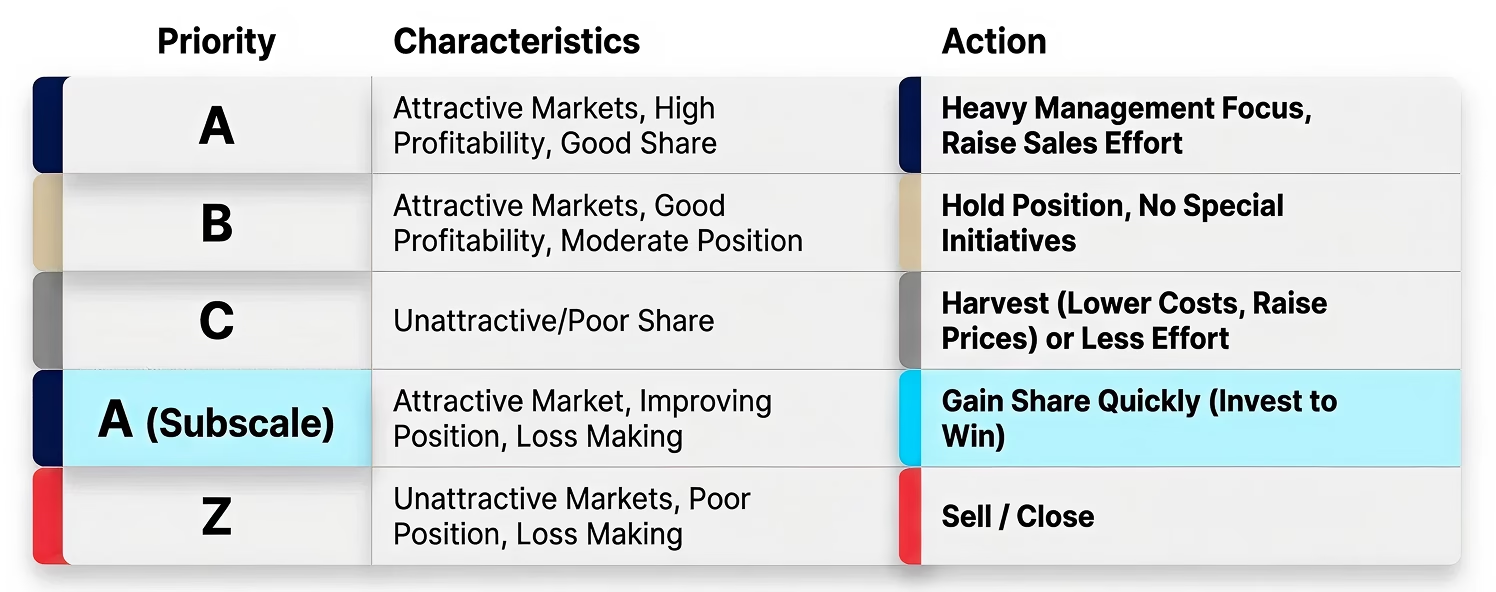

Take action: A strategy for every segment

Simple is Beautiful.

Complex is Ugly.

Executives love complexity. Once a business is successful, they cannot resist complicating it with marginal products, new customers, and layers of management. Complexity automatically makes a company less profitable. It reduces focus on what is simple and profitable.

Simple

To make a company more profitable, make it simpler. Then scale the new highly profitable business to the maximum.

Small is not beautiful. Simple and big is beautiful.

Progress requires simplicity. Simplicity requires ruthlessness. That is why simple is as rare as it is beautiful.

Complex

There is thus a natural tendency for business, like life in general, to become overcomplex. All organizations, especially large and complex ones, are inherently inefficient and wasteful. They do not focus on what they should be doing. They should be adding value to their customers and potential customers. Any activity that does not fulfil this goal is unproductive.

Yet most large organizations engage in prodigious amounts of expensive, unproductive activity.

Every person and every organization is the product of a coalition and the forces within the coalition are always at war. The war is between the trivial many and the vital few. The trivial many comprise the prevalent inertia and ineffectiveness.

The vital few are the breakthrough streaks of effectiveness, brilliance and good fit. Most activity results in little value and little change. A few powerful interventions have massive impact. The war is difficult to observe: it is the same person, the same unit and the same organization which produces both a mass of weak (or negative) output and a smattering of highly valuable output.

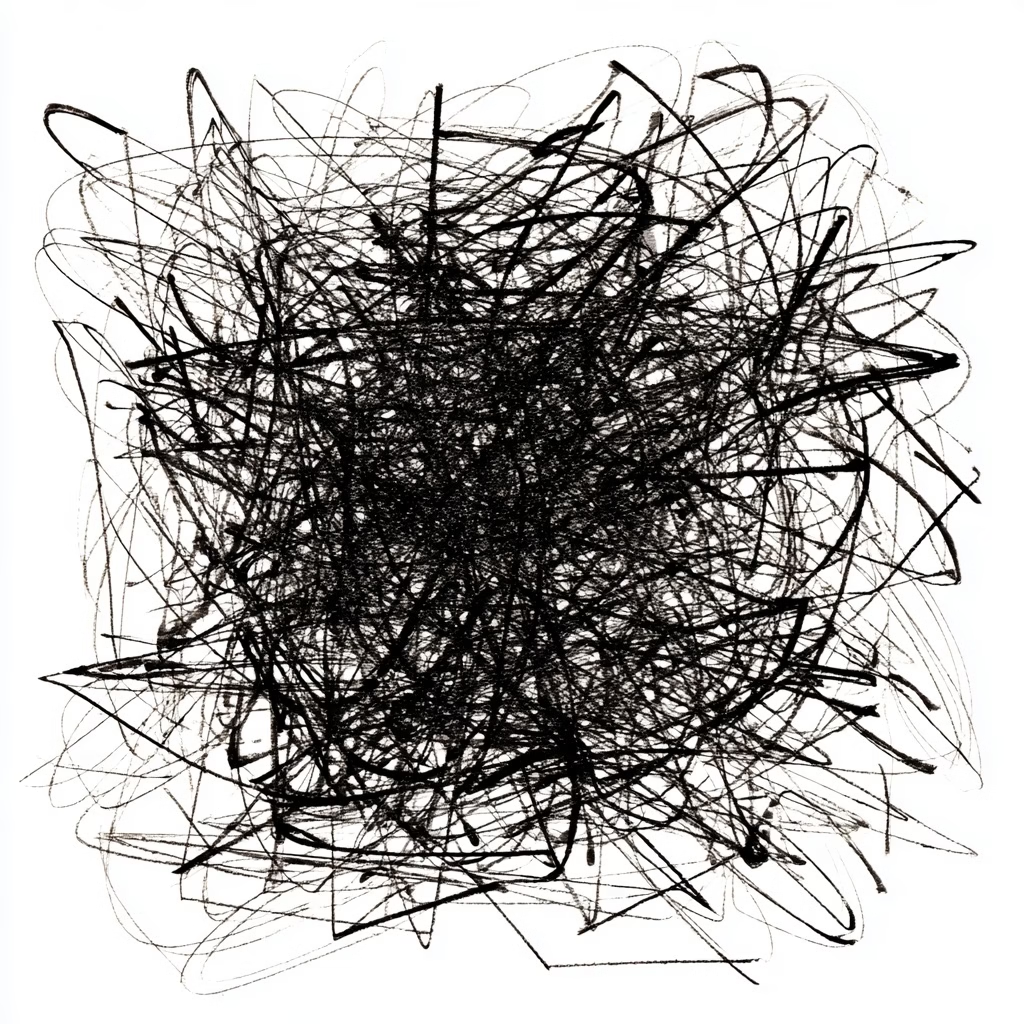

Once made more complex, a company automatically becomes less profitable. Complexity leads to taking on more marginal business and reduces the focus on what is simple and profitable.

The lamest excuse in business

“But we need the volume to cover overheads”

When confronted with 80/20 data, managers often argue that unprofitable segments “contribute to overheads”. This sounds reasonable. It is not.

The unprofitable 80% is unprofitable precisely because it requires overhead. The overhead exists to support complexity. Remove the complexity and the overhead can disappear with it.

The profitable 20%, by contrast, often requires very little central support. It is profitable because it is simple – and because it has been left alone.

What looks like shared cost is usually self-inflicted cost.

Managers assume

“If we remove revenue, overhead remains.”

The reality

“If we remove complexity, overhead collapses.”

Unprofitable segments do not merely fail to cover overheads. They cause them.

The Simplicity Playbook

Progress requires simplicity.

Simplicity requires ruthlessness.

This is why simple is rare – and why it wins.

01

Dismantle the hierarchy

If you are just in one line of business, you don’t need a head office, regional head offices or functional offices. And the abolition of the head office can have an electric effect on profits.

The key problem with head offices is not their cost. It is the way they take away real responsibility and initiative from those who do the work and add the value to customers. Corporations should center themselves around customer needs rather than around the management hierarchy.

In almost every 80/20 exercise, the most profitable parts of the business are those with the least central interference. This is not an accident.

02

Outsource everything but your genius

Most cost programmes fail because they preserve the shape of the business. They shave budgets while leaving complexity intact.

Outsourcing is a terrific way to cut complexity and costs. The best approach is to decide which is the part of the value-adding chain (R&D–manufacturing–distribution–selling–marketing–servicing) where your company has the greatest comparative advantage – and then ruthlessly outsource everything else. This can take out most of the costs of complexity and enable dramatic reductions in headcount, as well as speeding up the time it takes you to get a product to market. The result: much lower costs and often significantly higher prices, too.

When low-volume, unprofitable products are eliminated, capacity frees up. Overhead shrinks naturally. Profitability rises without heroics.

03

Rethink management incentives

Managers tend to like complexity, as complexity increases span of control and span of control increases status. This new found status resists simplification.

Complexity is also interesting and rewarding to managers. Particularly managers who are smart but more of less wholly focussed on administration (instead of sales or execution of operations). This results in an administrative management hierarchy creating complexity, that is tolerated long after it stops being affordable.

Unless an organisation faces crisis – or has an unusually customer- and investor-oriented leader – or the right incentives in place – complexity is almost guaranteed to grow.

04

Radically focus the business

Go for the 20%.

Concentrate on providing a stunning product and service to the 20% of customers who provide 80% of your profits.

Cut the number of products, customers, and suppliers to focus only on the most profitable. Standardise delivery of these products or services on as universal and global a basis as possible. Pass up thrills, bells and whistles. Make the profitable 20 percent as high quality and consistent as imaginable.

Whenever something has become complex, simplify it; if you cannot, eliminate it. This is essentially Elon Musk’s key tool for success.

The principle in Action: The Japanese Quality Revolution

The story

In the 1950s, the work of pioneers like Joseph Juran was largely ignored in the West. Japan, then known for shoddy goods, embraced their ideas.

The 80/20 application

Juran focused on the “vital few” causes that led to the majority of quality defects. By addressing this critical 20% of problems, Japanese manufacturers achieved an unprecedented leap in quality and productivity.

“For every step in your business process, ask yourself if it adds value or provides essential support. If it does neither, it’s waste. Cut it.”

The 80/20 Marketing Gospel

Focus on the small majority of markets and customers that are most profitable and enjoyable to serve, and have the highest growth potential. Provide a stunning product and service to this 20 percent.

The three golden rules are:

1.

Provide a stunning product / service

Marketing, and the whole firm, should focus on providing a stunning product and service in 20 percent of the existing product line – that small part generating 80 percent of fully costed profits.

2.

Focus on the top 20% of customers

Marketing, and the whole firm, should devote extraordinary endeavour towards delighting, keeping for ever and expanding the sales to the 20 percent of customers who provide 80 percent of profits.

3.

Focus where you are unique

You will only be successful in marketing if what you are marketing is different and, for your target customers, either unobtainable elsewhere, or provided by you with a better value proposition than elsewhere.

Be marketing led for the few right product / marketing segments.

Be customer centered for the few right customers.

Channel effort on where you offer something unique or much better value than peers

Saleperson

performance

Sales is marketing’s close cousin: the front line activity to communicate and, at least as important, to listen to customers. Take any salesforce and perform an 80/20 analysis. It is odds on you will find an unbalanced relationship between sales and salespeople.

Steps to re-engineer your salesforce for maximum impact:

Hang on to your high performers

Keep them happy. This cannot be done mainly with cash.

Hire more of the same type of salesperson

Personality and attitude are probably more important than qualifications.

Put your sales superstars in a room together and work out what they have in common.

Better still, ask them to help you hire more people like them.

Identify when the top salespeople sell the most and what they did differently

80/20 applies to time as well as people – what were they doing differently when they had a hot sales streak?

Get everyone to adopt the methods that have the highest ratio of output to input

Whether it’s advertising, networking, pro-active tailored focussed messaging, consistency, making phone calls –

Switch a successful team from one area with an unsuccessful team from another area

This will tell you if the good team can beat structural differences and vice versa.

Salesforce training

Invest in training the lower 80% of the salesforce. However (a) only train those who you are reasonably sure plan to stick around for several years and (b) get the best salespeople to train them – rewarding sales superstars according to subsequent performance of trainees.

Making structural Sales changes

A great deal of sales often depends on the quality of the products being sold, and the customers and markets being served.

Those in charge of salesforces should:

80/20 product focus

Focus every salesperson’s efforts on the 20 percent of products that generate 80 percent of sales. Make sure that the most profitable products attract four times the credit that an equivalent dollar of less profitable products does. The salesforce should be rewarded for selling the most profitable products, not the least profitable.

Lower cost service for less important accounts

Lower costs and use the telephone for less important accounts.

Centralise the smaller accounts and provide a lower cost touch and sales footprint for these. Less travel (face to face) and marketing effort on these.

Revisit old customers

Get the salesforece to revisit old customers who have provided good business in the past. This can mean knocking on old doors or calling old numbers.

An old, satisfied customer is very likely to buy from you again and again.

Organise the best accounts under the best team

Organize the highest volume and profit accounts under one salesperson or team, regardless of geography. Have more national accounts and fewer regional ones.

National accounts used to be confined to firms where one buyer had responsibility for purchasing all of one product, regardless of the location to which it went. Here it is plainly sensible to have an important buyer marked by a senior national sales executive. But, increasingly, large accounts should be treated as national accounts and served by a dedicated person or team, even where there are many local buying points.

Focus on the vital few customers

Focus salespeople on the 20 percent of customers who generate 80 percent of sales and 80 percent of profits. Teach the salesforce to rank their customers by sales and profits. Insist that they spend 80 percent of their time on the best 20 percent of customers, even if they have to neglect some of the less important customers.

Spend more time with the minority of high-volume customers should result in higher sales to them. If opportunities to sell more existing products have been exhausted, the salesforce should concentrate on providing superior service, so that existing business will be protected, and on identifying new products that the core customers want.

5 rules for decision taking with 80/20

Business requires decisions frequent, fast and without much idea if they are right are wrong.

1. Not many decisions are very important

Before deciding anything, picture yourself with two trays in front of you – like the dreaded in and out trays on a desk – one marked Important Decisions and one Unimportant Decisions.

Mentally sort the decisions, remembering that only one in five is likely to fall into the Important Decision box.

Do not agonize over the unimportant decisions and, above all, don’t conduct expensive and time-consuming analysis. If possible, delegate them all. If you can decide which decision has a probability of 51 per cent of being correct. If you can’t decide that quickly, spin a coin

2. The most important decisions are often those made only be default

This is because because turning points have come and gone without being recognise. For example,

- your chief money makers leave because you have not been close enough to them to notice their disaffection or correct it.

- Or your competitors develop a new product that you think is wrongly conceived and will never catch on.

- Or you lose a leading market-share position without realizing it, because the channels of distribution change.

- Or you invent a great new product and enjoy a modest success with it, but someone else comes along and makes billions out of a lookalike rolled out like crazy.

- Or the nerd working with you in R&D ups and founds Amazon

When this happens, no amount of data gathering and analysis will help you realize the problem or opportunity. What you need are intuition and insight: to ask the right questions rather than getting the right answers to the wrong questions. The only way to stand a reasonable chance of noticing critical turning points is to stand above all your data and analysis for one day a month and ask questions like:

- What uncharted problems and opportunities, which could potentially have tremendous consequences, are mounting up without my noticing?

- What is working well when it shouldn’t, or at least was not intended to? What are we unintentionally providing to customers that for some reason they seem to appreciate greatly?

- Is there something going badly astray, where we think we know why but where we might be totally wrong?

3. 80/20 the 80/20 analysis

The third rule of 80/20 decision taking is for important decisions: gather 80 percent of the data and perform 80 percent of the relevant analyses in the first 20 percent of the time available, then make a decision 100 percent of the time and act decisively as if you were 100 percent confident that the decision is right

4. Don’t be afraid to experiment or change your mind

Fourth, if what you have decided isn’t working, change your mind early rather than late. The market in its broadest sense – what works in practice – is a much more reliable indicator than tons of analysis. So don’t be afraid to experiment and persevere with losing solutions. Do not fight the market

5. Double down on winners

Finally, when something is working well, double and redouble your bets. You may not know why it’s working so well, but push as hard as you can while the forces of the universe are bending your way

80/20 Project management

Many of the most energetic people in business, from CEO down, do not really have a job: rather, they pursue a number of projects.

Four rules for successful project management

Project management is an odd task. On the one hand, a project involves a team: it is a cooperative and not a hierarchical arrangement. But, on the other hand, the team members usually do not know fully what to do, because the project requires innovation and ad hoc arrangements. The art of the project manager is to focus all team members on the few things that really matter.

Simplify the objectives

First, simplify the task. A project is not a project: almost invariably, a project is several projects. There may be a central theme in the project and a series of satellite concerns. Alternatively, there may be three or four themes wrapped up in the same project. Think of any project with which you are familiar and you will see the point.

Projects obey the law of organizational complexity. The greater the number of a project’s aims, the effort to accomplish the project satisfactorily increases, not in proportion, but geometrically.

80 percent of the value of any project will come from 20 percent of its activities; and the other 80 percent of activities will arise because of needless complexity. Therefore do not start your project until you have stripped it down to one simple aim.

Impose an impossible time scale

This will ensure the project team does only the really-high-value tasks.

Faced with an impossible time scale, project members will identify and implement the 20 percent of the requirement that delivers 80 percent of the benefit. Again, it is the inclusion of the ‘nice to have’ features that turn potentially sound projects into looming catastrophes.S

Impose stretch targets. Desperate situations inspire creative solutions.

Ask for a prototype in four weeks. Demand a live pilot in three months.

Plan before you act

The shorter the time allowed for a project, the greater proportion of time that should be allowed for its detailed planning and thinking through.

When Richard was a partner at management consultants Bain & Company, he proved that the best-managed projects we undertook – those that had the highest client and consultant satisfaction, the least wasted time and the highest margins – were those where there was the greatest ratio of planning time to execution time.

In the planning phase, write down all the critical issues that you are trying to resolve. (If there are more than seven of these, bump off the least important.) Construct hypotheses on what the answers are, even if these are pure guesswork (but take your best guesses). Work out what information needs to be gathered or processes need to be completed to resolve whether you are right or not with your guesses. Decide who is to do what and when. Replan after short intervals, based on your new knowledge and any divergences from your previous guesses.

Design before you implement

Particularly if the project involves designing a product or service, ensure you have the best possible answer in the design phase before you start implementation. Another 80/20 rule says that 20 percent of the problems with any design project cause 80 percent of the costs or overruns; and that 80 percent of these critical problems arise in the design phase and are hugely expensive to correct later, requiring massive rework and, in some cases, retooling.