In the short time since his inauguration on January 20, Trump has imposed, and sometimes walked-back tariffs on Canada, China and Mexico, and declared a policy of “reciprocity” for any foreign tariffs on American exports that are higher than U.S. tariffs on imports.

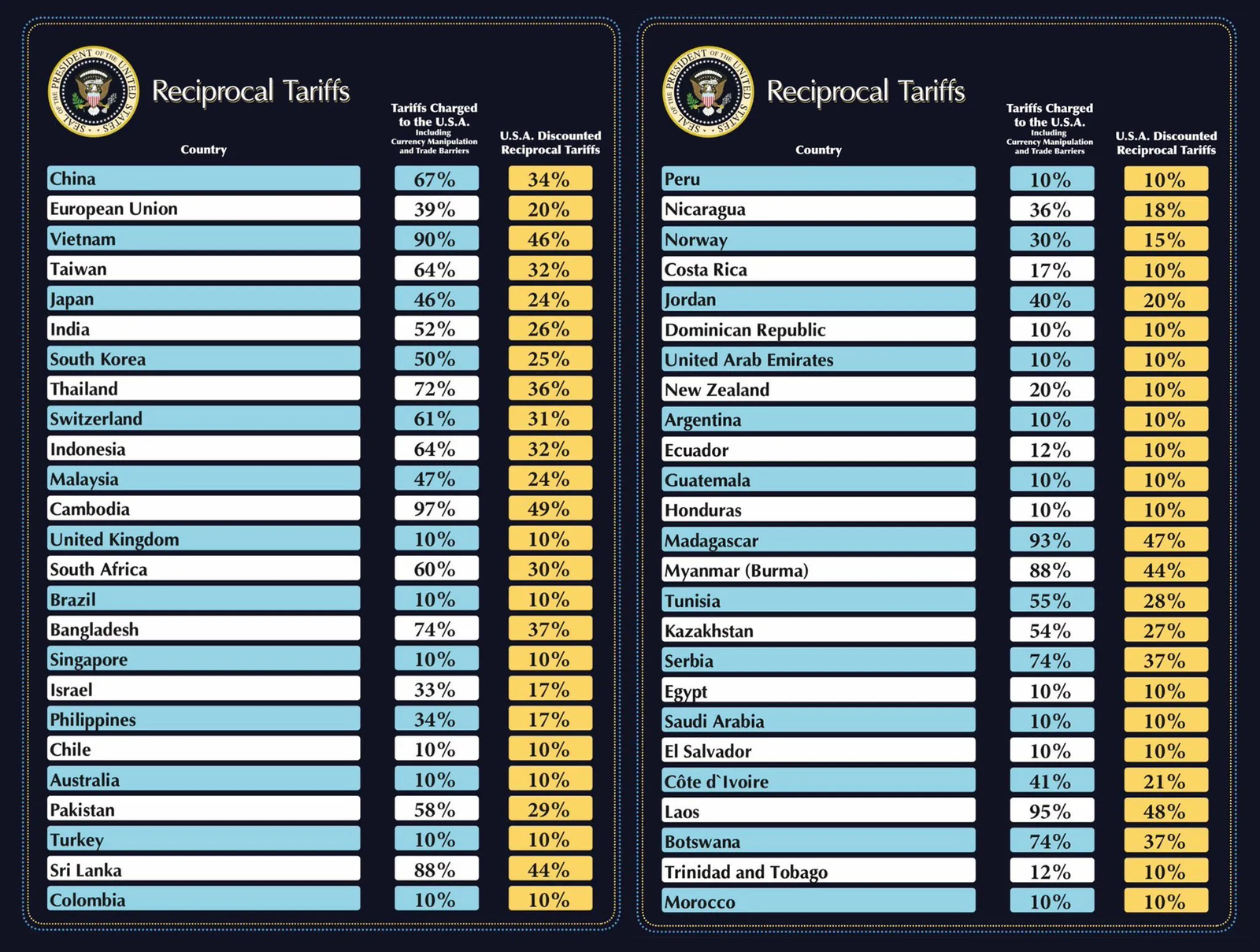

On 2 April 2025, ‘reciprocal’ tariffs were announced on almost all trading partners.

Key observations

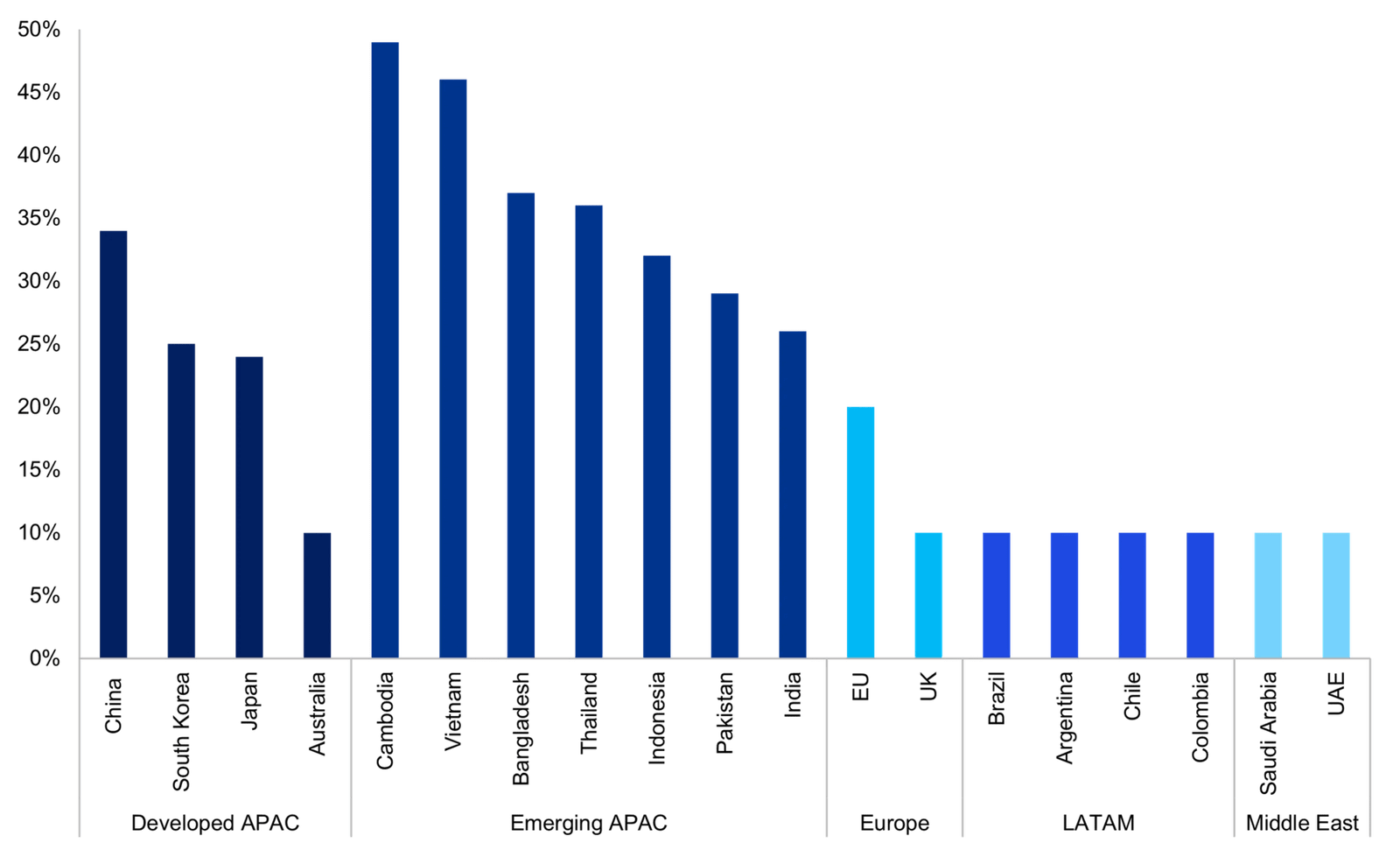

- 10% baseline of tariffs on all goods into the US with “reciprocal tariffs on over 90 countries effective April 5 or 9”

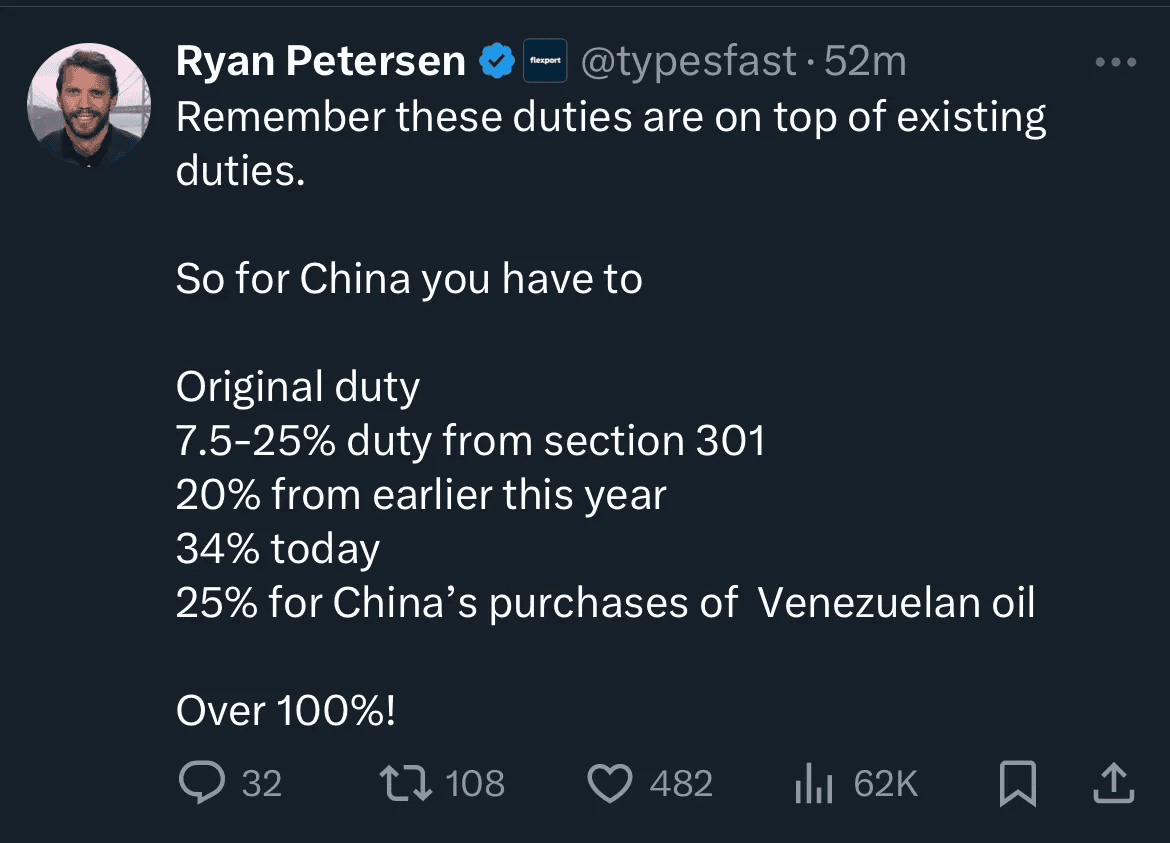

- China the worst hit – aggregate duties now over 100%

- LATAM favoured over Emerging Asia (10% duties in LATAM versus e.g. 46% for Vietnam)

- China + 1 supply chain strategies (which leaned heavily on ASEAN and Mexico) in disarray.

- Companies selling into the US, will need to reconsider LATAM for offshoring

Inconsistent narratives

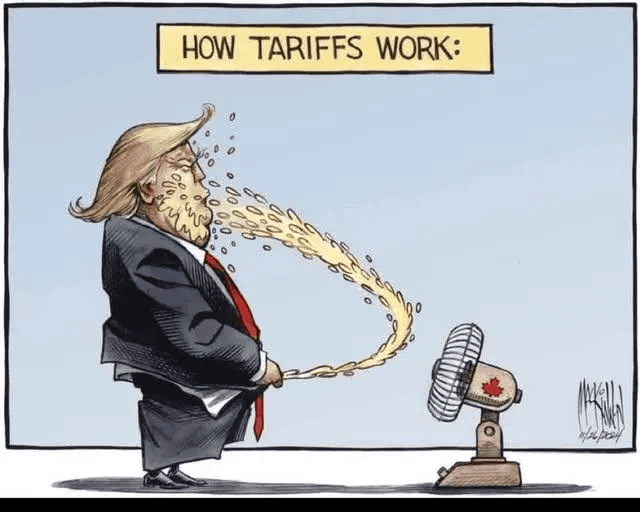

Trump has justified tariffs with **arguments** ranging from protecting or reshoring, to pressuring America’s neighbours to take action to reduce the cross-border flow of illegal immigrants and drugs. And also for balancing the budget. And for reciprocity. Some of these arguments are mutually exclusive – for example, reshoring means less revenue will be raised.

The inconsistent (chaotic?) communication has confused markets and enraged allies.

The Argument against Tariffs

Legacy media – NYT, BBC, FT, etc – will tell you tariffs are inherently misguided and inevitably harmful. If you surveyed a group of business people and academics on the merits of tariffs, the vast majority would tell you they were ‘dumb’, though their reasoning often falters. A few might cite David Ricardo’s‘Comparative Advantage’:

“If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry, employed in a way in which we have some advantage.” On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. David Ricardo, 1817.

Ricardo’s logic suggests tariffs hurt all sides by:

- Efficiency Loss: Tariffs push resources into industries where a country lacks comparative advantage, reducing total output. For instance, if the U.S. slaps tariffs on imported steel, it might prop up domestic steelmakers but at the cost of industries (like car manufacturing) that rely on cheap steel. This means US manufacturers will be less competitive abroad.

- Consumer Harm: By raising import prices, tariffs make goods more expensive for consumers. Ricardo uses a wine-and-cloth example which implies that if England taxes Portuguese wine, English consumers pay more, and Portugal has less incentive to buy English cloth, shrinking trade benefits (remember he was writing in 1817, when England had a leading textiles industry).

- Global Retaliation: Tariffs spark retaliatory measures.

In short, the argument is that tariffs warp efficiencies, shrink trade, and ultimately leave everyone poorer. Establishment rhetoric is pretty unanimous on this.

Steel-manning the other side of the argument

But, If free-trade is such a no-brainer, and tariffs are so dumb, why is there such a wide gap between wha the establishment says and actual government practice around the world?

Argument 1: Reciprocity

Large and persistent annual U.S. goods trade deficits are caused in substantial part by a lack of reciprocity in our bilateral trade relationships. This situation is evidenced by disparate tariff rates and non-tariff barriers that make it harder for U.S. manufacturers to sell their products in foreign markets. Executive Order – Regulating Imports with a Reciprocal Tariff, White House, 2nd April 2025

From North America to Europe to Asia, countries have long been ignoring mainstream economists and slapping tariffs onto imports in favored industries like electric vehicles and renewable energy.

The EU – probably the worst offender in terms of the double standard on free-trade speech and action – has tonnes of tariff and non-tariff barriers – red-tape, subsidies (think French agriculture) and foreign investment restrictions. Examples of EU tariffs in place: 38% on Chinese EVs, 25% on US Steel, and up to 50% on US Bourbon and Harleys. The EU is already mulling additional tariffs on China/Emerging markets due to the concerns of “dumping” via a diversion of trade from US markets

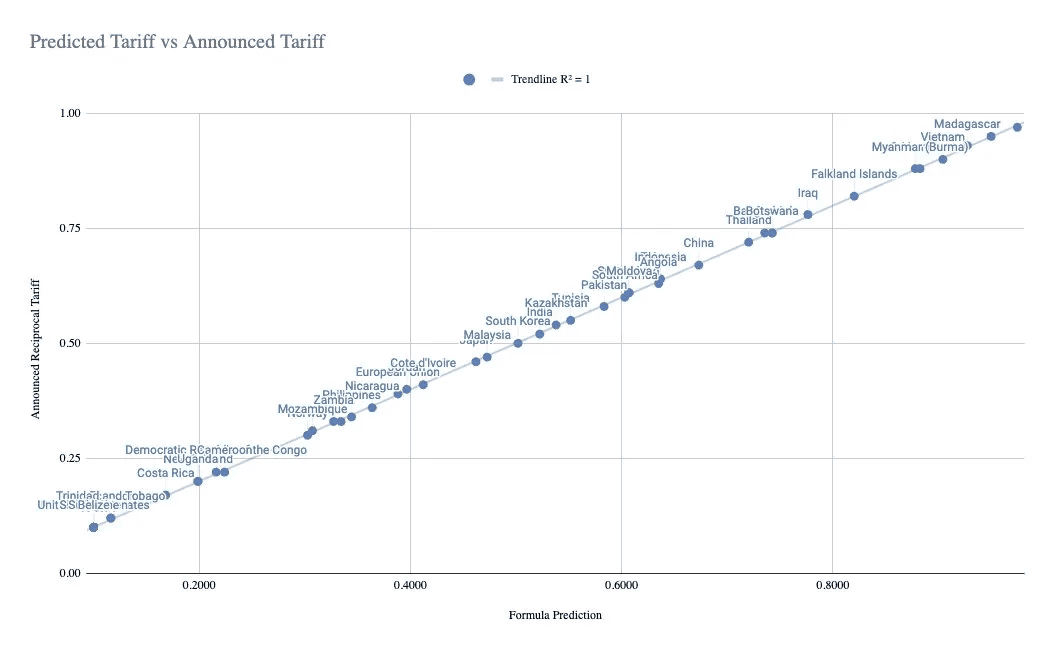

The US sees these tariff and non-tariff barriers against it, aiming to mirror 50% of them reciprocally. While the reciprocity concept is fine – the problem is that calculation of “Tarriffs Charged to the USA” in the table below was not done in a precise manner – it’s the nation’s trade deficit with the US, divided by the nations exports to the US, as proven from the below regression analysis.

This approach punishes trade deficits over restrictive policies, hitting export heavy but open economies unfairly.

If there had been a systematic study on effective tariffs in play and the impact of non-tariff barriers it would have made the US reciprocal tariffs far more compelling as a start point (in my opinion).

Given the way they have been calculated one assumes they are a “quick and dirty” start point for negotiations. Smaller emerging markets with “reciprocal” high tariffs, such as Cambodia, have already offered to cut tariffs on multiple categories as a start to negotiations.

Argument 2: De-industrialisation Fears

Large and persistent annual U.S. goods trade deficits have led to the hollowing out of our manufacturing base; inhibited our ability to scale advanced domestic manufacturing capacity; undermined critical supply chains; and rendered our defense-industrial base dependent on foreign adversaries. Executive Order – Regulating Imports with a Reciprocal Tariff, White House, 2nd April 2025

In many parts of the world governments are resorting to tariffs and industrial policy, not because they don’t understand Economics – Scott Bessent, the US Secretary of Treasury is widely to considered to be one of the best Macro investors in the world. Rather it’s because they do not want their economies de-industrialized by a flood of low-priced, state-subsidized imports, predominantly from China.

The evidence is in the numbers from other markets ex US. Canada has imposed a 100% tariff on Chinese electric vehicles, plus a 25% surtax on Chinese steel and aluminum. India’s gone further, with tariffs of 70% to 100% on EVs from China and elsewhere.

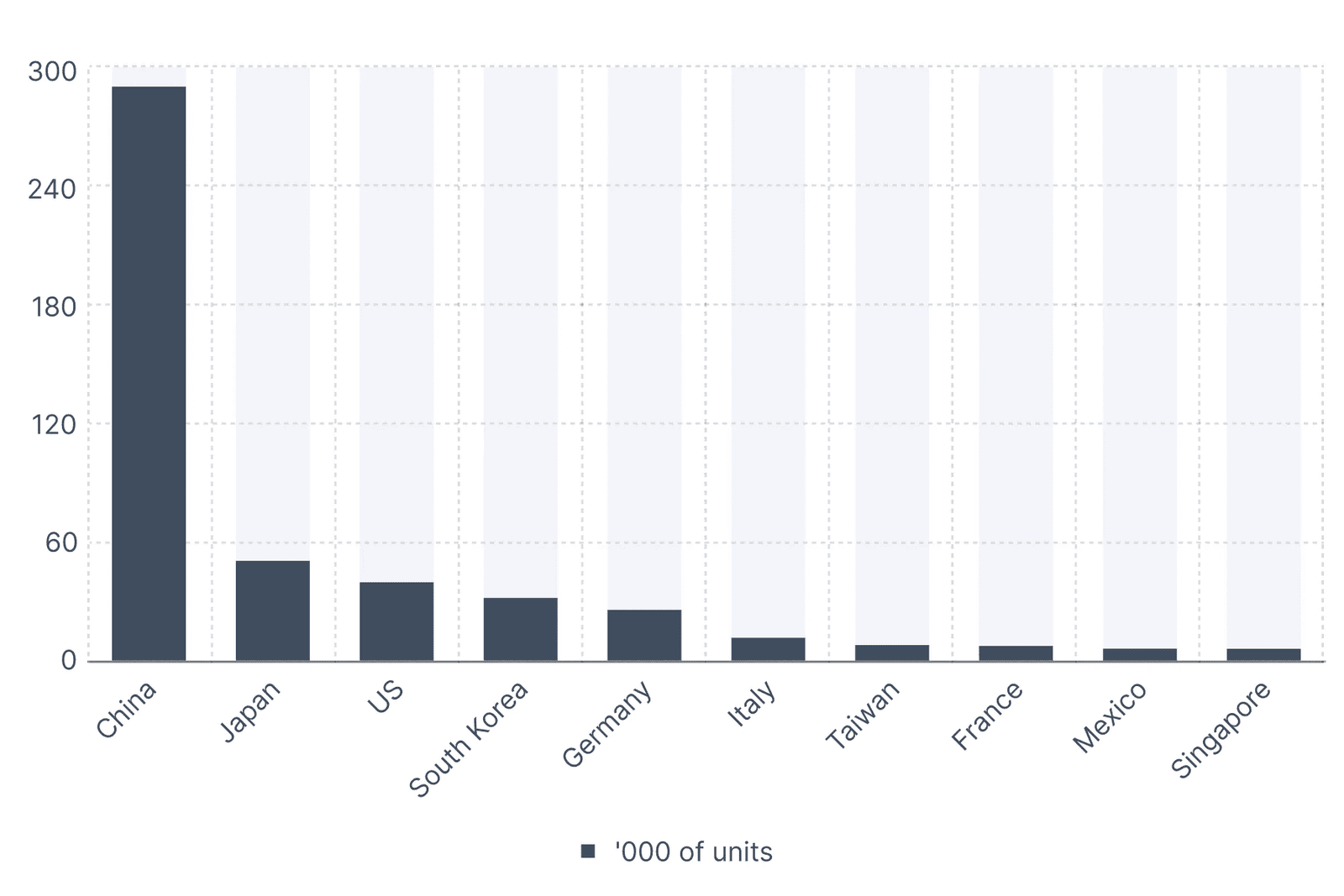

How did Chinese manufacturing dominance take root? Western companies, years ago, saw an opportunity in China’s lower costs and moved production there. The logic was straightforward – cheaper labor, better margins. At the same time Chinese government has invested for the long term in building national champions in key manufacturing segments, and world-leading infrastructure.

Over time, this has reshaped the global trade landscape. In 2023, China accounted for roughly 30% of global manufacturing value added, while the U.S. sat at 16%. The UK, once the cradle of the Industrial Revolution, has seen its industrial core shrink and is now one of the world’s most de-industrialized nation – partly due to its own policy choices, like the recent green energy focus.

Trade flows reflect the shift: China exports finished goods, while developed economies supply raw materials, agricultural products, or services like finance and tourism.

If the trend of industrial automation continues – another area where China has a massive lead – then a secondary concern is that cheap labour won’t be enough to give emerging nations a leg-up to follow China, Japan and South Koreas manufacturing rise. This is because cheap electricity and robotics will be a determining factor for national industrial competitiveness. A matter KPMG discuss in this article here:

Industrial robot installations (2022)

The worries about loss of industrial competitiveness isn’t abstract. There are very real and practical implications for jobs, innovation, and economic resilience. Another emerging consideration is military power balances, at a time of heightened geopolitical tensions. Europe and the US combined seem barely able to match Russia in production of ammunition and missiles etc.

I’ve been in mainland China this week, and traveling up and down the country on high speed rail which is clean, comfortable and runs on time; or driving into what used to be remote areas along pristine roads, and through miles of tunnels and over mountain high bridges – the level of infrastructure is actually quite awe inspiring. As is the advancement of the local auto industry – the look and feel of cars produced locally, at much lower costs, feels ahead of what you see from almost all American and European manufacturers. European and Japanese auto makers have lost share in China, not because they are more expensive – it’s because local consumers now see the made-in-china cars as a better product.

Argument 3: Fiscal gains

The post-war international economic system was based upon three incorrect assumptions: first, that if the United States led the world in liberalizing tariff and non-tariff barriers the rest of the world would follow; second, that such liberalization would ultimately result in more economic convergence and increased domestic consumption among U.S. trading partners converging towards the share in the United States; and third, that as a result, the United States would not accrue large and persistent goods trade deficits. Executive Order – Regulating Imports with a Reciprocal Tariff, White House, 2nd April 2025

Before 1913, the US had no income tax, and Tariffs provided the major component of fiscal funding. Amazingly, income tax was only introduced in the US to finance the 1st world war effort, and later the 2nd World War. Post-war, US tariffs stayed low to aid Europe and Asia’s recovery. At some point – with Japan or Germany’s resurgence by the late 1970s, tariffs could have returned, cutting US income tax.

If the US can cut income tax by levying tariffs – a stated outcome – then the US will lure entrepreneurs and business to reshore, which will attract innovation and spark growth.

Steelman conclusion…

Tariffs, then, aren’t necesarily a rejection of free markets – they’re a pragmatic attempt to level the playing field after years of uneven global shifts and double standards on trade.

Where do i stand?

I’m conflicted. I was educated in the Ricardo / traditional principles of economics, and like the elegance of the Comparative Advantage argument. But I’m cognizant that invisible hands and economic theories don’t always work in practice – especially when countries tip the scales through tariffs, trade barriers, subsidies and so on.

I view Scott Bessent – and his mentor, Stanley Drunkenmiller – are two of the smartest brains in real world economics – so I wouldn’t want to bet against this US Administration achieving their stated objectives. To be clear, these priorities to do not include lifting of share prices of listed companies – rather they are weighted to reducing debt through a combination of cutting government spending, increasing revenues from tariffs, and refinancing short term US notes at better rates.

Leaving aside the merits for one minute – what are some of the likely impacts?

Likely first-order impacts

- Trade flows: US trade drops; China’s shift to ASEAN, Middle East, Africa and LATAM speeds up. China and Emerging market trade also reorientated to other developed markets without tariffs

- Emerging Nation Renegotiations: Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia, etc, with weak leverage, must cut tariffs – they won’t get away with just doing this for the US. The EU and China will demand the same, hitting local champions in these markets.

- Retaliation from stronger, more developed nations: China has already retaliated with 34% counter-tariffs. The path forward with China is escalation ****and tension. Europe will implement face-saving tariffs but will want to negotiate.

- Inflation in the US / Deflation in some other markets: Goods with no cheap US substitutes will rise in price; barrier free markets may see deflation from redirected trade.

- Market chaos: We’ve already seen material stock market and commodity market movements and this volatility will continue. The Vix (volatility index) is at an all time high.

Possible second-order impacts

- Emerging Asia crisis: AI and robotics and already eroding the competiveness of low-cost manufacturing which relies on cheap labour; tariffs are likely to place extreme pressure on export orientated SMEs in Emerging Asia. There will significant restructurings needed in these markets if deals are not done rapidly.

- Certain business collapses in the US: US manufacturers dependent on international supply chains are going to see immediate increases in production costs eroding margins. It could take many years for substitute inputs to be manufactured in the US, so the only choice will be to either procure cheaper replacement parts than those currently used, try and pass on costs (though this will be challenging) or see material declines in margins.

- Policy rethinks: If US Tariffs “win” – i.e. more revenue, jobs, domestic manufacturing etc in the US – other developed economies will need to rethink trade policy.

- Supply chain shifts: China plus one policies falters; LATAM gains, Asia loses on tariff gaps

- Reshoring: Developed market governments tweak energy (more nuclear, less ESG) and infrastructure investment (ports, trains, roads) to revive manufacturing

Industry specific impacts

- Automotive: Auto manufacturers in the US which are a higher proportion domestic made (e.g. Ford at 80%), benefit over those which are import reliant (e.g. GM at 45%).

- Consumer goods and retail: major eCommerce downturn for players such as Amazon, Tmall, Temu, Shein which rely on duty free from low cost manufacturing hubs to sell into the US. New tarriffs, and perhaps more importantly the removal of de-minimus duties from May 2025, are going to slash demand and cross-border GMV. eCommerce enablement platforms and logistics companies like Shopify and DHL will feel it too.

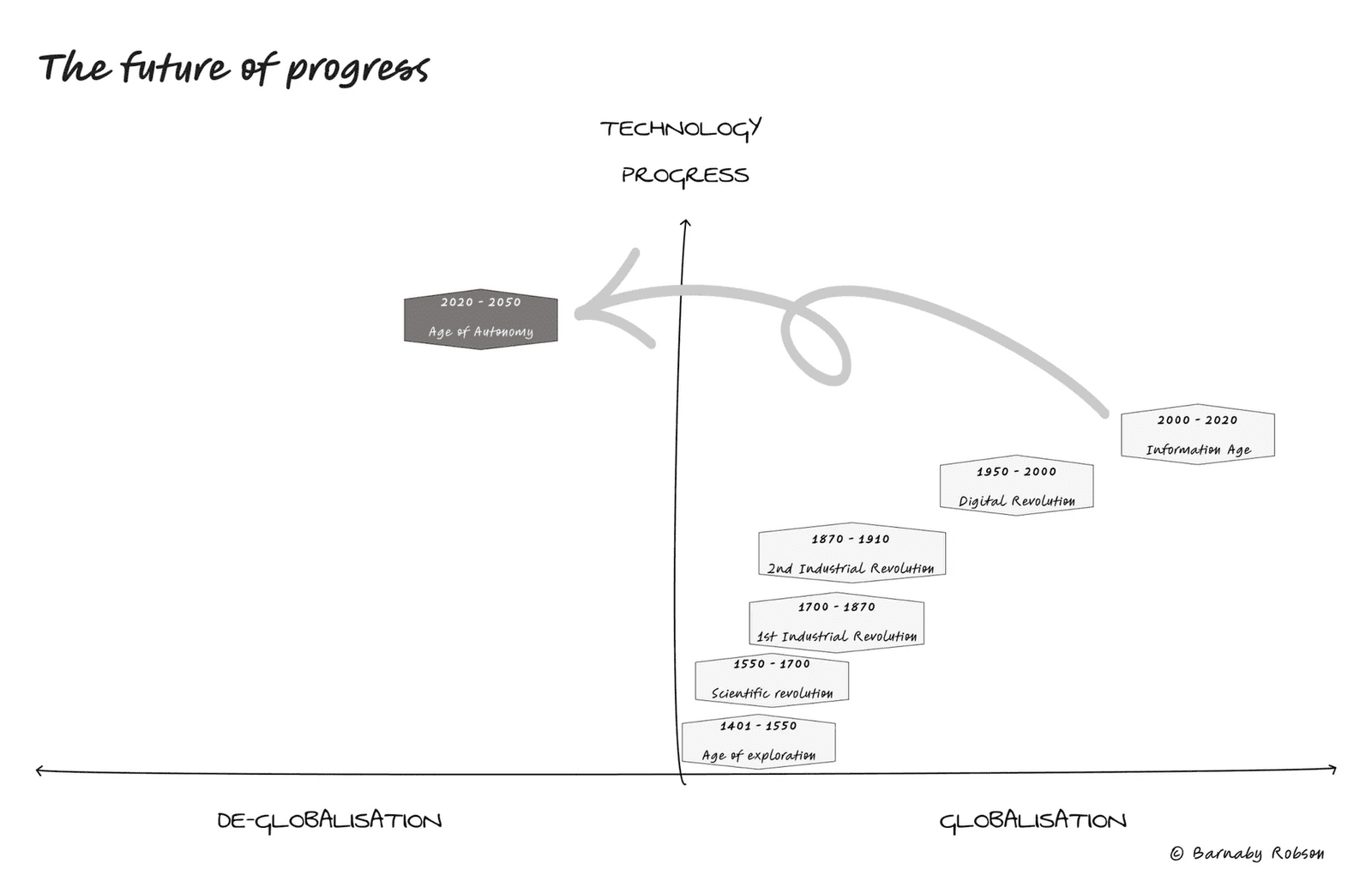

A fundamental reshaping

Trump’s tariffs challenge the free-trade system Britain built in the mid-19th century. Back then, as the world’s industrial titan, Britain championed free trade to flood markets with its industrial goods. Today, as the US swings to isolationalism, we’re seeing a fundamental reshaping of that order. I discussed this in this article here – but we’re seeing twin trends of deglobalisation and technology acceleration. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/future-progress-barnaby-robson?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_ios&utm_campaign=share_via

What happens next is very hard to predict – it really depends on whether there is a grand renegotiation and leveling of the playing field on trade, or if countries decide to counter and errect new barriers.

What is clear is that supply chains will need to bend, emerging markets will feel strain and global power will shift. This will impact all countries and companies. Agility to adapt will be key – and industries with flexible supply chains (e.g. auto) may adapt faster.

Some will believe that policies will be reversed in four years, with a new US administration and try and wait things out. I think for the reasons articulated above, the changes in trade policy have been a long time coming and those forces will not reverse with different parties in power – indeed, the Biden administration was as tough as Trump on China trade.